Location: New York, NY

Age: 57

Marital Status: Married

Education: BA, English, Boston University; MA, American Studies, City College of New York

I often say that I was born in 1944 but raised in the 15th century, because although I was born in Waterbury, CT, a New England factory town, post-WWII, I grew up in a large southern Italian family where the rules were absolute, and customs antiquated. My sister and I were doing the jitterbug to Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” coming from the radio on the kitchen counter, my father was singing Nat King Cole songs in the shower and my grandfather was singing “Vicin’ ‘O Mare,” and “Non sona più la sveglia” under the grape arbor.

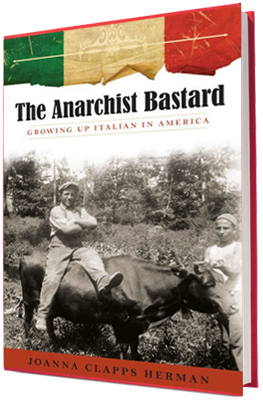

So begins Joanna Herman’s memoir, The Anarchist Bastard, which chronicles her coming of age in an Italian immigrant family on a farm in Waterbury, Connecticut. The ensuing 244 pages paint a portrait of her iron-worker father, homemaker mother, and an extended family overflowing with legends, customs, food, animals, wisdom, comedy and tragedy. The writing is so rich and the stories so colorful that you have to remind yourself you’re reading about events in New England, and not in the “backwater” towns of Tolve and Avigliano, in Basilicata, Italy—where the clan’s routes can be traced. We chatted with Joanna about the incredible push-pull she felt from her family—and how she learned to negotiate it and make her life her own.

One of the most prevalent themes in the book is how tight-knit your large family was—almost like the Marines. How would you describe it?

Your family is crucial. If somebody needs you, you run at the drop of a hat. That is the work of your life. To be a cohesive unit. You have a beautiful social group when you’re relaxing, eating… That’s the appeal of it; you’re never lonely. The thrill of human communion is always there.

What is the main drawback to all this family closeness?

Ambition is frowned upon. You’re not supposed to want for yourself—only for the greater good. I’d arrive home from college, and my mother would immediately go, ‘My hairdresser’s daughter just had a baby; we have to go over there.’ I mean, ‘What?!’ When I was in grad school, working on a paper about my family’s culture, I found out my dad had had a heart attack. He was okay, but my mom expected me to drop everything and tend to him, even if it meant failing out of school. Here I was, studying the roots and drawbacks of that mentality, and it was being impressed upon me at the same time.

Why is the culture like that?

Our ancestors were constantly being invaded. Basilicata is this peninsula that sticks out in the middle of the Mediterranean, with ports everywhere and a road up to Europe. It was the perfect place for everyone to invade. The Pheonicians, the Carthiginians. The Greeks. The Etruscans. Everybody came, took all their goods, married or raped their women… So the indigenous people turned inward, further and further, to protect themselves from their new bosses. They sacrificed their individuality to find strength in numbers.

Would your grandparents have shared that theory—on why the culture is so insulated?

They’d say: ‘[We’re like that] because we’re poor. We’re real low. The most remote, most isolated, and poorest.’ They would have stopped there, without looking for the deeper roots of it. Whatever you grow up doing, and continue doing your whole life, is so close to you. You don’t think about it in the same way you might if you stepped back from it. It took me a long time to discover why my family was like that.

When did you begin to realize it?

I went to Tolve and D’avinagno with some of my family in 1964. We walked into that town and I thought, “Oh! I see! I see why my mother does that.” We couldn’t walk ten yards without a dozen people accosting us, asking who this person was, what that person was up to. In New York, I might have thought, ‘I don’t know these people. What business is it of theirs?’ And it was like that all day, every day. That was the beginning of being able to see it all from a distance. Seeing how deeply connected we were to the customs of this old country, where there was no individualism.

Is it still so old-fashioned over there?

Not totally. Today in Italy, you see these little old ladies, then you see their granddaughters with punk orange hair, and they’re walking arm in arm. Italy is able to incorporate both old and new and keep them integrated. But here, we didn’t know how to integrate it. We came with our ancient ways, and everything was ancient, modern, ancient, modern. Bringing the old customs over and integrating them at the same time was too much for the first generation.

Like how your mother wanted you and your sister to go to college, but your father wasn’t as enthusiastic.

My mother was not allowed to go to college and she wanted to go desperately. My grandmother wouldn’t even let her go to Hartford overnight for bookkeeping training. But my father had made some good money, and she saw an opening. ‘My girls are going to college,’ she told him. Then her brothers would say, ‘Why are you sending those girls to college? They think they’re so smart? They don’t even know how to milk a cow.’ My father assumed that as soon as we graduated, we’d come back home. He sat down with my mother one day and said, ‘When are the girls coming home, Rose?’ She had to tell him, ‘Peter, they’re not.’ He sobbed for hours and hours.

What was it like when you finally left Connecticut?

After I moved to New York in the late sixties, it took me a long time to even figure out how disoriented I was. Decades. At first, I was living in the village, soaking up the sixties. Sex, drugs and rock and roll. I started working, I became a teacher. But the whole time, I didn’t notice that underneath it all was this thing that was confusing me. “Why doesn’t this work? Why doesn’t that work?”

What do you mean? What didn’t work?

At a certain point, I began to realize I didn’t have the same chops my friends all had. My way of moving in the world was skewed. For example, if I wanted to move up at work, my first thought was to have the right people over to dinner. That should work, right? Shouldn’t that be the way networking worked? I didn’t have the sense that it more about me, what I accomplished alone. My world was all about family—not about ambition. Raising [my son] James gave me so much perspective, because looking at him, I knew I wanted different things for him. My life did not belong to me, until my mother died.

How did you pass the family values to your son, without letting him fall into that trap?

It was tough, and I don’t think I did at first. My son loves my family, he loves that culture. But it’s caused him trouble. It pulls on him. And I have to bear in mind that I don’t want it to suppress him. He’s the next generation of trying to figure it out. He still runs to my husband Bill and me when we need something—but, too much so. Sometimes I have to tell him, ‘No, James. You need to focus on your work.’ Ironically, it took James growing up for me to finally gain the full perspective that I needed to write this book.

How’s that?

This joyous, delicious, complicated center of my life was preparing to leave the harbor. And all I could see was the empty slip. I had been reading and playing with writing all my adult life. But it was the fear of his leaving and feeling totally emptied out that made me say, ‘Get back to that machine and start writing now.’ I started spending twelve hours a day at my computer. Hours and hours. I had this new ambition.

Do you ever miss it—being so wound up in a large family like that?

Sometimes. I’ve never had that same pulsing life again. The thrill of the day-to-day. You could be laughing, you could be crying, but you always felt fully alive. There’s a loneliness to my life here in New York. I get together with friends, but it’s arranged. Life is arranged in New York. Back there, it was provincial. But I like my life like this, no question.

What would your old school relatives have thought of this book?

They would have been appalled. Maybe not all of them. At one of my readings, my aunt Antonia told me, ‘Your mother would have been so proud.’ For her to say that was such a huge deal to me. She didn’t even like my mother.

What is your favorite book?

War and Peace and The Odyssey. Both are epic. And Tolstoy is emulating Homer.

How do you rejuvenate?

I swim. There’s a pool in Riverdale I try to get to three times a week.

Do you have a favorite New York doctor you’d recommend?

Dr. Iris Sherman, on Columbus Avenue in Manhattan. She cares about her patients. She calls you herself, not her assistant.

Beauty salon?

Ada Ballen at Tipaz, on West 57th.

Restaurant?

Pisticci. The food is sensational. Or New Leaf in Fort Tryon Park. When you sit down there, you might as well be in Italy or France.

Please visit www.joannaclappsherman.com for more information on readings and other events, and to order The Anarchist Bastard.