I was beside myself with joy when I made the Arista National Honor Society in high school. I remember running down the hallway of Francis Lewis with excitement. I couldn’t wait to call my dad when I got home later in the day, because this was the era before cell phones. Way, way before.

Aside from that, I can’t think of an “award” I’ve won that thrilled me nearly as much. Generally, awards are created so organizations and businesses can bring in revenue by selling exhorbitantly priced tickets to those who feel they are obligated to “pay homage” to the person winning the award. And, we all know about awards like the Oscars, which rarely have much to do with the actual talent of the honorees.

Aside from that, I can’t think of an “award” I’ve won that thrilled me nearly as much. Generally, awards are created so organizations and businesses can bring in revenue by selling exhorbitantly priced tickets to those who feel they are obligated to “pay homage” to the person winning the award. And, we all know about awards like the Oscars, which rarely have much to do with the actual talent of the honorees.

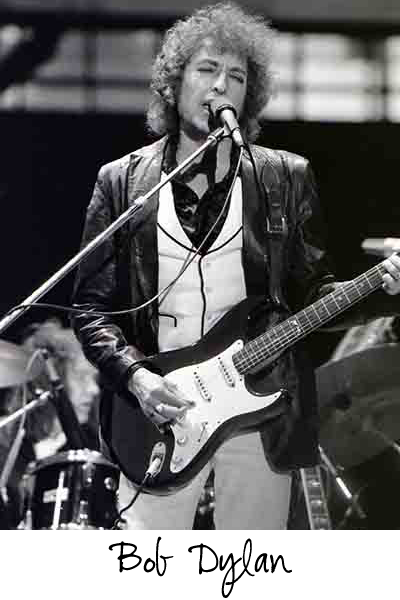

Occasionally, award winners turn down their honors. Remember when Bob Dylan refused to accept his Nobel Prize for Literature last year? Marlon Brando boycotted the Academy Awards in 1973, when he won a Best Actor Oscar for his role in The Godfather, because he didn’t like the way the film industry treated Native Americans. Entertainers aren’t the only ones who turn down awards. Physicist Stephen Hawking reported he turned down a knighthood in the 1990s, purportedly because he objected to the UK government’s mismanagement of science funding.

Recently, 46-year-old Sebastien Bras, one of France’s most celebrated chefs, asked the executive committee that awards the prestigious Michelin stars to restaurants all over the world to take away his eatery’s coveted three stars. Reviews of restaurants, with and without stars, appear in the Michelin Guide.

Recently, 46-year-old Sebastien Bras, one of France’s most celebrated chefs, asked the executive committee that awards the prestigious Michelin stars to restaurants all over the world to take away his eatery’s coveted three stars. Reviews of restaurants, with and without stars, appear in the Michelin Guide.

Sebastien took over the restaurant, Le Suquet in Southern France, from his father a decade ago, subsequently retaining the three stars his dad won in 1999. He said he’s “fed up with the pressure of maintaining those stars and is seeking culinary liberation,” according to the article I read in the New York Times.

Michelin Guide inspectors visit restaurants, unannounced, two or three times a year, and would only sample a small number of his dozens of dishes, Sebastian told a reporter from the NYT. “‘Three stars mean that everything must be perfect, at any time, in every plate,’ added Yves Bontoux, a consultant for six French Michelin-starred restaurants. “‘One must be passionate, a genius, but mostly a workaholic, because you have to be working in your restaurant from 7 a.m. to 2 a.m. every day, nonstop,’” the article said. Besides the personal stress involved in maintaining a three-star Michelin rating, it taxes a restaurant’s budget to maintain high-end decor and an impeccable staff.

“‘Food should be about love–not about competition,’” Sebastien explained. “All I want is to welcome people to my restaurant during the day, or during the night under a sky filled with stars.’”

Back in the day, the New York Times theatre and food critics could make or break a show or restaurant with a single review. I once had dinner in Chicago with a NYT restaurant critic, as a matter of fact, and she didn’t even recognize that the soup had sherry in it. No one’s perfect. I’m going to guess that bad moods even hit Michelin inspectors when they’re out on assignment. It happens to the best of us. Or, maybe one or two of them are just meanies.

Back in the day, the New York Times theatre and food critics could make or break a show or restaurant with a single review. I once had dinner in Chicago with a NYT restaurant critic, as a matter of fact, and she didn’t even recognize that the soup had sherry in it. No one’s perfect. I’m going to guess that bad moods even hit Michelin inspectors when they’re out on assignment. It happens to the best of us. Or, maybe one or two of them are just meanies.

I admire Sebastien! It’s unlikely he’s going to let the quality of his restaurant’s cuisine slide one bit. And, who cares if patrons eat off stoneware plates, rather than fancy Limoges?