{FOF Book Critic & Giveaway} Summer reads from Linda Wolfe

I’ve been trying to evade New York City’s heat wave (and an apartment full of chores) by holing up out East in Sag Harbor, with little to do – lucky me! – but relax, swim and read, read, read. Here are some of the books I’ve found particularly interesting this summer.

I’ve been trying to evade New York City’s heat wave (and an apartment full of chores) by holing up out East in Sag Harbor, with little to do – lucky me! – but relax, swim and read, read, read. Here are some of the books I’ve found particularly interesting this summer.

FOF award-winning author, Linda Wolfe, recently published her powerful book, MY DAUGHTER/MYSELF, in June. She has published eleven books and has contributed to numerous publications including New York Magazine, The New York Times, and served the board of the National Book Critics Circle for many years. Her latest reviews take you from the 1970s art world to a remote Afghani village; a gay artist during the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s to a Cherokee migrant worker in the 1930s.

Win one of these summer reads! To enter, comment below by answering the question: Which of Linda’s picks do you want to read?

THE FLAMETHROWERS. Rachel Kushner. Scribner. 383 pp.

THE FLAMETHROWERS. Rachel Kushner. Scribner. 383 pp.

Motorcycles! Lovers! The heady 1970s. The cool art scene in lower Manhattan. The sizzling urban guerilla scene in Italy. Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers is a coming of age story about Nevada-born Reno, a motorcycling enthusiast, who comes to New York, an innocent abroad, so to speak, makes friends among the art world’s cleverati – painters and filmmakers whose conversation is as abstract and difficult to fathom as their work – falls in love with painter Sandro de Valera, scion of a wealthy Italian family that manufactures motorcycles, gets betrayed by Sandro, and loses some of her previous befuddled naivete. Along the way she races a motorcycle on the Salt Flats of Utah, poses as a model for a New York company that produces film stock, goes to Italy, falls out with Sandro and in with members of Milan’s Red Brigades, and becomes an artist herself, a “land artist”– a practitioner of the art of creating patterns and designs on the earth’s surface.

Kushner is a gorgeous writer. The muse doesn’t just inspire her, it colonizes, inhabits her, making thoughts and images flow from her pen in a seemingly unstoppable flow. Some of the writing is exquisite. Of New York in winter, Kushner writes “Water jeweled itself to a clear, frozen dribble from the fire hydrant in front of my building.” Of Milan, she observes, “Neon was electric jewelry on the lithe body of the city;” Lake Como is “a spill of silver;” Utah’s Great Salt Lake has “white drifts [that] looked almost like snow but they moved like soap, quivering and weightless.”

But Kushner can also be wordy and imprecise. Here she is, stumbling toward describing how when we become adults, we still retain remnants of our girlhood selves: “It was not the case that one thing morphed into another, child into woman. You remained the person you were before things happened to you. The person you were when you thought a piece of cut string could determine the course of a year. You also became the person to whom certain things happened. Who passed into the realm where you no longer questioned the notion of being trapped in one form. You took on that form, that identity, hoped for its recognition from others, hoped someone would love it and you.”

Worse, Kushner can be insufferably boring because she enjoys making the reader realize how insufferably banal some of her characters are by reproducing lengthy passages of their pretentious conversation. She is also a devotee of the post-modernists’ distaste for chronology, starting her story with Reno’s motorcycle race, then taking the reader back in time to her meeting Sandro and his circle, then on to the motorcycle race again, then forward once more, to the trip to Italy. But she interrupts even this confusing structure with chapters about Sandro’s father, the founding of the Valera company, and oddments about domestic terrorists in sixties New York. Toward the end, this speed-obsessed book swerves and nearly crashes.

Still, Kushner has been highly touted by a multitude of critics, called the voice of her generation, and “one of the most brilliant writers of the new century.” Give the book a whirl, get into the conversation, and see what you think.

LOVE, DISHONOR, MARRY, DIE, CHERISH, PERISH by David Rakoff. Doubleday. 116 pp.

LOVE, DISHONOR, MARRY, DIE, CHERISH, PERISH by David Rakoff. Doubleday. 116 pp.

When’s the last time you read a novel in verse? I hate to admit it, but I think the last one for me was The Iliad, in my college days. So I was totally unprepared for the experience of reading this playful, highly original, laugh-out-loud funny, yet deeply moving first novel written in rhyme by David Rakoff, essayist and frequent presence on the radio show This American Life.

Rakoff, who died of cancer at the age of forty-seven worked intensively on Love, Dishonor for the last months of his life, writing between bouts of chemotherapy and surgery, and encountering ever-increasing weakness. Still, determined to finish the book, his first novel, finish it he did, about a week before he died.

The novel links the lives of seven characters who live in various American locales and in various decades. It starts with a child born to a superstitious, rejecting mother in turn-of-the-19th-century Chicago, and ends in present-day New York with a man whose wife, unfairly blaming him for the failure of their marriage, has left him and taken their children.

The infant, named Margaret,

had hair on her head

Thick and wild as a fire, and three times as red

The midwife, a brawny and capable whelper,

Gave one look and crossed herself, God above help her.

The abandoned husband is living in a tiny studio apartment:

It struck him as fitting, a concrete admission

Of guilt: one’s apartment as form of punition.

In such a bare space, he might do some soul-healing.

With room for the boxes, stacked from floor to ceiling.

There is also a woman, “neither widow nor wife,” with a husband whose stroke has left him helpless, an office worker, once a glowing Aphroditic beauty but now middle-aged, and single, in love with her married unresponsive boss, and – most touchingly – Clifford, a talented gay artist who contracts AIDS in epidemic-stricken 1980’s San Francisco. As his illness worsens, Clifford, the voice of the author:

thought of those two things in life that don’t vary

(Well, thought only glancingly: more was too scary).

Inevitable, why even bother to test it.

He’d paid all his taxes, so that left…you guessed it.

Clifford, like Rakoff, dies tragically young:

The inkwell tipped over and spread ‘cross his page.

Clifford was gone. Forty-five years of age.

The connection between the novel’s various characters is indirect but, once revealed, thrilling. The rhymes are witty, ingenious. And the poet proves to be a soulful chronicler of our human joys and sorrows

AND THE MOUNTAINS ECHOED by Khaled Hosseini. Riverhead. 404 pp.

AND THE MOUNTAINS ECHOED by Khaled Hosseini. Riverhead. 404 pp.

If you haven’t already read Khaled Hosseini’s beguiling And the Mountains Echoed, you should. More complex than The Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns, it nevertheless moves like the wind, sweeping the reader along through decades of Afghanistan’s troubled history. But the history here is not one of wars and invasions and political turmoil. “I need not rehash for you [our] dark days,” says a doctor who has come to Kabul to tend to people grievously wounded in the country’s chaos and serves in a major section of the book as the voice of the author. “I tire at the mere thought of writing it, and, besides, the suffering of this country has already been chronicled. And by pens far more learned and eloquent than mine.” Rather, the history in And the Mountains Echoed is that of ordinary people, Afghanis and visitors to Afghanistan whose lives flourish or fail in the dark days and intersect in oblique and fascinating ways.

Hosseini is enormously skilled. The book begins with the story of a ten-year-old Afghan boy, Abdullah, who has been looking after his sister, Pari, ever since their mother died in childbirth. As an example of the author’s skill, from the moment we meet the sister, he doesn’t have to tell us that Pari is a much younger child. Rather, he shows us the girl, unable yet to correctly pronounce her brother’s name, calling out “Abollah!” whenever she wants him.

Pari is, as it turns out, three, and when the children’s poverty-stricken father allows a childless upper class woman to adopt her, Pari’s cry of “Abollah! Abollah!” as she is torn from her brother, is heart-wrenching.

The separation of the children is prefigured by a folktale, one of many in the repertoire of the children’s father, about a long-ago time when a giant dwelled on the earth and could demand and carry off a poor family’s child. The stolen children are not, as their families fear, killed or, worse, consumed, by the giant, but allowed to grow up in luxurious circumstances, live like princes and princesses in a landscape of gardens and twinkling streams, surrounded by music and poetry and fed with delectable food. But the children forget their parents, and the father in the tale, who discovers the whereabouts of the kidnapped boys and girls, is given a glimpse of his own stolen child but then given, too, out of the kindness of the giant’s heart, a potion that will make him forget what he’s seen and indeed never remember his child at all.

This tale haunts the book, which is filled with stories of separation,

of partings caused by poverty, war, or ordinary human selfishness and self-absorption.

In the case of Pari and Abdullah, Pari is taken away to live in Paris by her adoptive mother, and grows up ignorant of her true parentage. Yet all her life she feels “the absence of something, or someone, fundamental to her own existence. Sometimes it was vague, like a message sent across shadowy byways and vast distances, a weak signal on a radio dial, remote, warbled. Other times it felt so clear it made her heart lurch….I was like the patient who cannot explain to the doctor where it hurts, only that it does.” Abdullah eventually emigrates to the United States, where he opens a tiny California restaurant called Abe’s Kebab House and, although having some modest success, never feels altogether happy. Or rather, he always feels somehow incomplete, and all his life hides beneath his bed his fondest treasure, a box of bird feathers he had collected in his boyhood to give to his sister if he ever saw her again.

When Abdullah’s wife gives birth to a daughter, he gives the child the name of his beloved sister. Little Pari grows up believing, like many little girls, she has an imaginary friend, but hers is an aunt named Pari, with whom she shares her dreams and worries.

The first Pari and her brother never meet until they are elderly, when they are brought together by the younger Pari. By the this time the first Pari suffers from severe arthritis and Abdullah, like the father in the folktale, has Alzheimer’s and cannot recognize, or even remember, the sister whose removal from his care has soured his whole life.

You’ll cry at the story of this brother and sister. You may cry, too, at the story of Pari and Abdullah’s father, deprived by a warlord of his meager property, or at that of Nabi, their uncle, who flees village life to become a servant. Or at the story of the hidden homosexual who for the sake of convenience marries the woman who adopts Pari. Or that of Thalia, a Greek girl who cares for the mother of the home-evading altruistic doctor in Kabul. Hosseini is a master at tugging on a reader’s heart strings.

More, all his stories here circle around that ancient folktale of familial separation. Such separation is a major torment in today’s world for the many immigrants from poor nations who must leave their families behind to work in – and hopefully send money home from – industrialized countries.

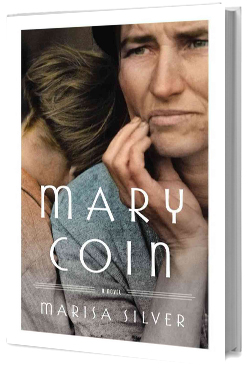

MARY COIN by Marisa Silver. Blue Rider Press, 322 pp.

MARY COIN by Marisa Silver. Blue Rider Press, 322 pp.

In the mid-nineteen-thirties a photograper working for the Federal Resettlement Administration snapped a haunting picture of a worn and desperate-looking woman surrounded by her young children, eyes staring worriedly into space at what she seemed to envision as a miserable future. You’ve seen the photo. It has become emblematic of the Great Depression and its millions of victims. Frequently exhibited in museums and galleries, copies of it are on posters and even on tee-shirts everywhere.

But who was the woman? And why was she so worried? The photographer’s name was Dorothea Lange. The subject of the photo was a woman called Florence Owens Thompson. But that tells us precious little. And it was the absence of information about the photo’s subject that inspired novelist and story writer Marisa Silver to write Mary Coin, her graceful and engrossing fictional exploration of the story behind the famous photo.

The story is told by three characters, Vera Dare, a photographer, Mary Coin, a migrant worker, and Walker Dodge, a professor of cultural history with a penchant for digging up the artifacts of everyday men and women. But it is Mary’s story that makes this novel so effective.

Silver’s Mary is born into a Cherokee family living on a farm in the Midwest. A daring and bright young girl, she dreams of a future that will get her away from the drudgery of farm life, a handsome prince who will carry her off and upward. She finds him in the son of wealthier neighbors, they fall in love, marry young, and migrate to California, arriving just when the depression strikes. They manage to land jobs picking fruit and vegetables on California estates, but they have children and are barely getting by when her husband succumbs to pneumonia and dies. From then on, Mary’s life goes from bad to worse.

She is now the sole support of her brood, and must take ever more demeaning and arduous picking jobs. These become more scarce as more and more migrant workers pour into California (think Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.) and Mary’s life is filled with almost unbearable poverty and misery – both of which she faces with an undauntable spirit. Mary also encounters Vera Dare, who like the woman her character is based upon, had polio as a girl, lived a bohemian life in San Francisco as a young woman, had numerous unhappy love affairs, and became a photographer, first of society figures but later, during the depression when clients became fewer and far between, a government -hired photographer of the poverty-stricken. Mary also has an affair – hers with the son of the owner of a ranch who may or may not be the grandfather of Walker Dodge, a secret that gives the novel momentum.

Did I say The Grapes of Wrath above? In fact Silver’s portrait of Mary Coin far exceeds anything in the Steinbeck novel, where the characters seem merely embodiments of propaganda. Mary, on the other hand, seems to live and breathe on the page. She makes this novel a powerful achievement.

Win one of these summer reads! To enter, comment below by answering the question: Which of Linda’s picks do you want to read?

![]()

1 FOF will win. (See official rules, here.) Contest closes August 1, 2013 at midnight E.S.T. Contest limited to residents of the continental U.S.