Are You A ‘Kissing Cousin’?

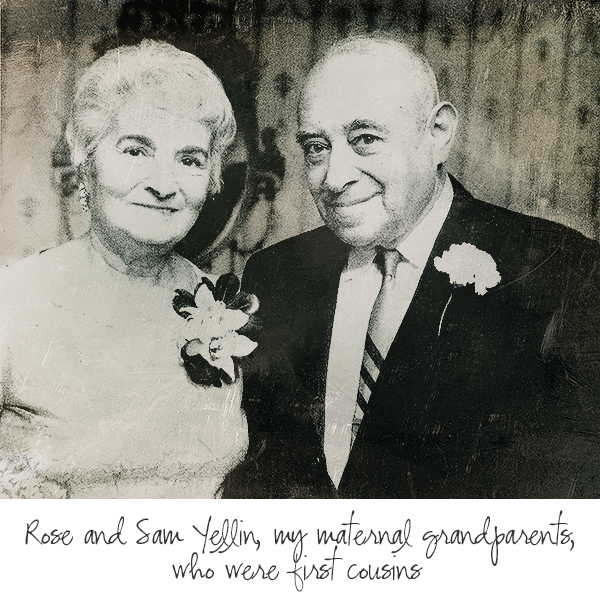

My maternal grandparents were first cousins. Ever since I learned this bit of notable family history, when I was a kid, I’ve heard the relationship defined as ‘incestuous’ and ‘illegal,’ and that it could have produced genetic disorders in my grandparents’ children (my mother, May, and her brother, Norman).

Fortunately, there were no genetic disorders, but my mother and her brother, along with their spouses (namely, my dad and my aunt through marriage) consciously decided to become neighbors when they bought their first houses in 1950. Called semi-detached homes, these modest structures had separate entrances, backyards and side yards, but shared a center wall. So my sisters and I grew up right next door to our one girl and two boy cousins. There is a 10-year gap between my youngest sister (now 61) and my oldest cousin (now 71).

Physical and chronological proximity aside, we were anything but “kissing cousins.” Our families never shared meals in one another’s homes, not even holiday repasts; we never vacationed together; we never went to the movies together, dined out together or celebrated graduations together. Except for attending my cousins’ weddings, and they ours, we might as well have grown up on different planets. We’d come a long way from our marrying cousins, a.k.a. our grandparents. We didn’t dislike our cousins, but our parents didn’t promote camaraderie and we didn’t take the initiative to get together on our own.

Whenever I heard about my friends’ “cousins club” get-togethers, I’d be secretly overjoyed I never had to attend one.

These “clubs” were big in the 50s and 60s, offshoots of clubs originally formed in the early part of the 18th century to serve large European immigrant families struggling to make it in America while trying to care for those in the ‘old country’  who hadn’t made the trip. Cousins clubs transcended ethnicity. Poles, Italians and Jews all benefitted from family closeness and generosity.

who hadn’t made the trip. Cousins clubs transcended ethnicity. Poles, Italians and Jews all benefitted from family closeness and generosity.

No wonder my grandparents’ generation was so cousin-centric. But even though my parents and uncles and aunts didn’t have to rely on extended family to support them in any way, why would so many of them not even lift a finger to promote friendship among their children? Especially when we lived practically cheek-to-jowl.

My two children have only four first cousins, but none of them are close either. Like our parents, my sisters and I haven’t done much to promote friendship between our children. We can throw around excuses, such as not living near one another, different lifestyles and vastly different demands on our time. But those are empty excuses. We just didn’t do it.

Besides, just because you grew up under the same roof as your siblings, doesn’t mean you’re all going to be best friends, or even friends at all. So who says your kids have to even recognize each other when they pass in the street?

Your thoughts?

P.S. Nine well-known people who married their first cousins: Charles Darwin, Albert Einstein, HG Wells, Edgar Allan Poe, Andre Gide, Igor Stravinsky, Jesse James, Rachmaninoff, and Wernher von Braun.

All of those popular people who live hedonistic lives of pleasure, I will destroy, because they never accepted me as one of them. I will kill them all and make them suffer, just as they have made me suffer. It is only fair.”

All of those popular people who live hedonistic lives of pleasure, I will destroy, because they never accepted me as one of them. I will kill them all and make them suffer, just as they have made me suffer. It is only fair.”