Do You Keep Your Vulnerabilities To Yourself?

If you openly admit that it’s impossible for you to get through a day without a glass (or three or four) of wine, do you think everyone will suspect you’re an alcoholic?

If you tell your boss that you don’t understand her instructions about executing a project, do you suppose she’ll think you’re stupid?

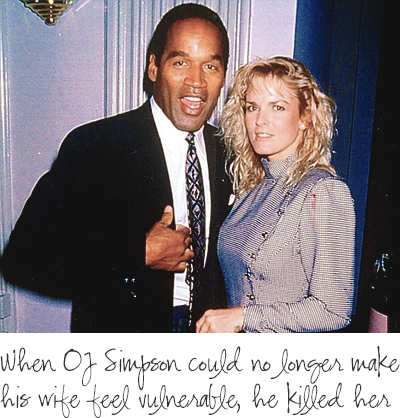

If you acknowledge to your sister that your husband often flies off the handle and slaps you, but you don’t react, do you expect she’ll tell you to leave him immediately?

Why do many of us think that the act of admitting we feel defenseless makes us look weak, when, in fact, it can be a sign of strength?

If you seek advice and guidance from a friend, a therapist, your husband—rather than letting a problem eat at you and possibly destroy your sense of wellbeing—aren’t you actually respecting yourself? I say it’s smarter to solve a problem than to pretend it doesn’t exist , or to anxiously mull it over and over, with no resolution in sight.

When I first went to a psychiatrist, at 17, my parents didn’t tell a soul. My father and I would surreptitiously leave the house when my mother was playing mahjong with her friends. I wonder where the ladies thought my dad and I were going at 8 PM on a Tuesday night. My parents couldn’t have the neighbors think they had a crazy daughter. How did that make them look?

Thank goodness, many more people today seek help, whether from therapists, their church, support groups like AA, their family or their friends. Yes, help often fails.  It’s consistently reported, for example, that over 85 percent of those who go through drug or alcohol rehab fail and return to their addictions. But, without help, where would the 15 percent be?

It’s consistently reported, for example, that over 85 percent of those who go through drug or alcohol rehab fail and return to their addictions. But, without help, where would the 15 percent be?

Even when our vulnerabilities involve issues other than drugs or alcohol, say intense insecurity about our relationships or career, there’s really no shame in discussing it. I know someone who privately thinks he’s a failure because his girlfriend earns a great deal more than he does, and he’s developed a bitter attitude about almost everything and towards almost everyone. If only he’d recognize that his feelings of defeat have nothing to do with his girlfriend’s earnings and try to move on. His girlfriend, in the meantime, constantly coddles him because she can’t stand to see him depressed.

This begs the questions: What is our role when we see someone we love being consumed

by his or her own vulnerability?

Do we start by quietly offering advice? Do we stage an intervention? Do we walk away from her because she is harming, not only herself, but her friends and family? Do we ignore it completely?

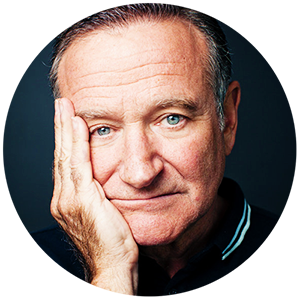

When I heard about the death of Robin Williams, I couldn’t help but ask myself why those physically and emotionally closest to him—his wife and manager, for example—couldn’t see impending disaster. And, if they did, why did they leave him alone for even a minute? But I know these questions are naïve. Although Robin Williams admitted his vulnerabilities, for years, to millions of us, and sought treatment on more than one occasion, his brilliant, crazy, funny, distracted mind apparently spun completely out of whack. The only way he could control it was to permanently turn it off. No one could stop him.