When my former father-in-law was bedridden with congestive heart failure, at 96, he asked his son (my ex) to help him end his life. Douglas contacted the Hemlock Society, a national right-to-die organization founded in 1980, to get a blueprint on how to carry out his father’s wishes. Douglas then asked if I’d be there while he did the deed. I said “yes,” despite the fact that it made me terrifically apprehensive (as it did him.)

When my former father-in-law was bedridden with congestive heart failure, at 96, he asked his son (my ex) to help him end his life. Douglas contacted the Hemlock Society, a national right-to-die organization founded in 1980, to get a blueprint on how to carry out his father’s wishes. Douglas then asked if I’d be there while he did the deed. I said “yes,” despite the fact that it made me terrifically apprehensive (as it did him.)

Douglas’ father, unbeknownst to me and Douglas, told his nurse about the plan; thankfully, the nurse wrote an email to his boss about it and copied Douglas. I say thankfully because if we had actually gone ahead with the plan, and then someone reported what we had done, we would have been charged with homicide.

I would not be a model prisoner, nor would Douglas.

Such is the unfortunate way the law works in the United States, in all but five states (Washington, Oregon, California, Vermont and Montana), when it comes to making a decision about ending your life. Even if you’re in extreme pain–physically or mentally–and you desperately want someone to help you put yourself out of your misery, no one can. Not your husband, your son, your best friend, or any doctor. You’d have to move to one of the states where “assisted suicide” is legal.

Diane Rehm and her husband, John, faced this issue, first hand, when Parkinson’s Disease took away John’s ability to feed himself, walk from the bed to the bathroom, bath himself or take care of himself, in any way. He asked Diane to bring together his physician daughter, academic son, and doctor to tell them:

“I am ready to die and I want you to help me.”

“Legally, morally and ethically, I can’t do anything.” the doctor responded.

“But dad, we can keep you comfortable,” John’s daughter added.

“I don’t want comfort. I am ready to die. I can no longer care for myself in any way. I am falling into degradation and I know that what lies ahead is further degradation, and I am not willing to go there,” John said.

“The only thing you can do is to stop eating, stop taking meds and stop drinking water,” the doctor advised John. “You can live a very long time without food, but without water the organs of the body start breaking down very quickly.”

Diane didn’t know what John was going to do, she recounts in her revealing and touching book, On My Own, which discusses her life, her marriage, the struggles of her dear husband with Parkinson’s, her struggle to reconstruct her life without him, and the aid-in-dying cause to which shes now devoting herself.

Diane didn’t know what John was going to do, she recounts in her revealing and touching book, On My Own, which discusses her life, her marriage, the struggles of her dear husband with Parkinson’s, her struggle to reconstruct her life without him, and the aid-in-dying cause to which shes now devoting herself.

When Diane returned the next day to see John at the assisted living facility where he was residing, he told her, “I have begun the journey. I had nothing to drink and nothing to eat, and the nurses were instructed not to bring me any medications.”

“I asked him if he was sure that this was what he wanted,” Diane clearly remembers. “And he responded that he was ‘certainly sure.’”

“John was fine for the next two and a half days, and then he drifted off into sleep. It took 10 long days for him to go and I was enraged,” Diane said.

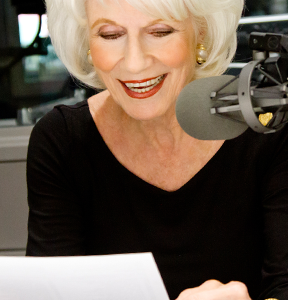

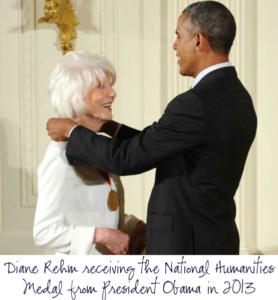

I had the opportunity to hear Diane, first hand, talk about her book and her aid-in-dying mission when she was interviewed recently by Jeffrey Rosen, president and CEO of the National Constitution Center. The subject of the conversation was Do Americans Have The Right To Die? Diane, by the way, has hosted The Diane Rehm Show in Washington, D.C.–distributed by National Public Radio–since 1979. The nationally syndicated show enjoys a weekly listening audience of 2.5 million. “Diane knows more than anyone about eliciting the subtleties, nuances and emotions of the most-pressing national issues,” Jeffrey said when he introduced her.

I had the opportunity to hear Diane, first hand, talk about her book and her aid-in-dying mission when she was interviewed recently by Jeffrey Rosen, president and CEO of the National Constitution Center. The subject of the conversation was Do Americans Have The Right To Die? Diane, by the way, has hosted The Diane Rehm Show in Washington, D.C.–distributed by National Public Radio–since 1979. The nationally syndicated show enjoys a weekly listening audience of 2.5 million. “Diane knows more than anyone about eliciting the subtleties, nuances and emotions of the most-pressing national issues,” Jeffrey said when he introduced her.

John Before Parkinson’s Disease

“We stayed together for 54 years, through thick and lots of thin. I totally believe that no marriage is perfect. People are not perfect and marriage is not perfect; ours was not, but it was one where we both clearly adored each other. We were very very different people.

“John was a US State Department attorney in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. He helped to create the office of the US Special Trade Representative and because its first general counsel. John left government in 1968 and joined a private law firm. After working for 40 years as an attorney, he decided at 71 to retire, against my better judgement, because I was continuing to work. He took a full year to study Asian Art and became a docent of the Freer and Sackler Gallery in DC, a reader for the blind and dyslexic, and a volunteer for hospice.

“John was a US State Department attorney in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. He helped to create the office of the US Special Trade Representative and because its first general counsel. John left government in 1968 and joined a private law firm. After working for 40 years as an attorney, he decided at 71 to retire, against my better judgement, because I was continuing to work. He took a full year to study Asian Art and became a docent of the Freer and Sackler Gallery in DC, a reader for the blind and dyslexic, and a volunteer for hospice.

“John would wait for me to come home to walk in our neighborhood, where we lived for 40 years.”

When Parkinson’s Struck

“All of a sudden I heard a shuffle when we walked. John also had three accidents in his bright yellow VW bug and our insurance was about to be cancelled. I wanted him tested.

“‘I wonder how your husband is going to feel when I tell him he shouldn’t be driving any longer,’ the doctor told me.

“John was actually relieved. ‘It wasn’t fun to drive anymore,’” he said.

Photo Credit: NBC News

“Four years after John retired, in 2005, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. After a back operation, he became more debilitated and had lots of tremors. He had been 6 feet tall, with huge broad shoulders because he worked in his father’s rock quarry in the summers. He looked like a football player. But he went from 180 to 130 pounds.

“It was a long journey. We decided to move to a condo, and one night I woke up and found John lying on the floor in front of the bathroom. I managed to get him onto his knees and drag him to bed, then inch by inch, and limb by limb I got him into bed. That night, we decided he would have to move to assisted living, and that’s where he died, in 2012.

Diane Speaks Out About Our Right To Die

“If we had moved to Oregon, two doctors would have had to decide that John was within six months of dying; he would have had to wait it out to establish residency; a psychiatrist would have had to examine him to determine if he was of sound mind, and, finally, he would have been given the medication that he could take to end his life.

“If we had moved to Oregon, two doctors would have had to decide that John was within six months of dying; he would have had to wait it out to establish residency; a psychiatrist would have had to examine him to determine if he was of sound mind, and, finally, he would have been given the medication that he could take to end his life.

“Interestingly, two-thirds of those who get these meds actually use them. But it allows them to be in charge of their own lives. They can say, ‘my life is in my own hands.’

“I am totally an advocate for the right to choose, and for me that feels very, very comfortable. If you believe that God is the only deciding factor in making the choice when you will go, I will support you. If you say I want no treatment, I will support you. And if you want to exercise your right to die, I will support you. I would argue that the right to die is so singular and so personal that it belongs ONLY to the individual, not to a state legislator. The state legislatures are too slow, and baby boomers facing their parents’ and their own mortality are so far ahead of them that we’re going to see a movement.

“My model to deal with the pain and suffering is not to have a six-month wait. If I personally decide that my physical and/or emotional pain is so great that I choose to die, and I am not in any way coerced, I should have the right to die. If I have a stroke or a heart attack in my own apartment, I will not call 911. I do not want to end my life in a hospital bed, intubated, surrounded by people I don’t know. I want to stay in my own bed.

“My mother died at 49 of liver disease, when I was 19. She never drank except at Christmas and New Year’s. She looked like she was 11 months pregnant and they kept draining the fluid from her. ‘Why, why don’t they let me die?’ she asked. John’s mother took her own life at 92 because her back and hip were so hurting her so bad and she had refused, at age 80, to have that hip replaced. She had gathered enough medication; she left each of us notes; she never told us she was going to take her own life.

“We need to have this conversation with our parents before they lose their competency and it’s too late. We are going to need people to demand the right to make their own decisions whether their lives are worth living.”