Am I a voice of one? I’ve never felt that what often goes by the title “Summer Reading” in magazines and online book review sites is what I want to read in the summer. What I want in the summer isn’t a so-called beach book, the kind you are inclined to throw away or press “Remove from Device” on your Kindle as soon as you’ve read it. What I want to read in the summer, what I save to read in the summer, are books with some meat on their bones, so to speak. Here are some that I’ve found succulent indeed so far this summer, not one of which I’m going to throw away, though I might just part with a couple temporarily, to lend to a friend with the proviso that she’d better return them or the friendship’s over. Wham, bam. We’re done, ma’am. Better yet, I’ll probably tell her to go and get the book herself.

Want to win a copy of one of these books? To enter to win, comment below by answering the question: Which of these books do you want to read and why?

FOF award-winning author, Linda Wolfe, has published eleven books and has contributed to numerous publications including New York Magazine, The New York Times, and served the board of the National Book Critics Circle for many years.

In The Light of What We Know

by Zia Haider Rahman

FSG. 497 pp.

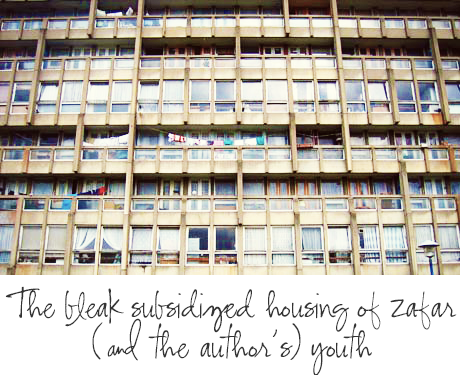

This one, like they say about turning fifty and entering upon those challenging decades that lie ahead, ain’t for sissies. Inventive and erudite, In the Light is a debut novel by Zia Haider Rahman, whose family emigrated to England from Bangladesh when he was a young child. Displaced, impoverished, often hungry, the author lived for a time in a rat-infested condemned London building until his father got a job as a bus driver and moved the family into subsidized housing. Young Rahman, despite all the odds against him, flourished, was so intellectually gifted and industrious a student that he won a scholarship to Oxford, where he studied mathematics,  and subsequently became an investment banker, then a human rights lawyer, and now, a novelist.

and subsequently became an investment banker, then a human rights lawyer, and now, a novelist.

Not much happens in this extraordinary novel. That is, what matters is what has already happened, and how its two main characters, talk about what has happened. The families of both are originally from Southeast Asia, though one, the nameless narrator, is from a privileged third-generation family, and the other, Zafar, from a background very like that of the author himself. Friends since their college days—both were at Oxford, both studied mathematics—the pair became bankers, and prospered professionally. But they haven’t seen each other in some years. And now a gaunt and haggard Zafar has arrived unexpectedly at the narrator’s posh home.

Reunited, he and the narrator talk at length in brilliant, analytical, digressive dialogue about all manner of things, from the financial crisis of 2008, to the war in Afghanistan, to sex, manners, love, betrayal, and most tellingly, about the ways class affects and afflicts one’s outlook on life. “No one talks about class anymore,” Zafar tells the narrator, “not since the death of socialism.” But class “is you, it’s the eyes with which you see the world.”

It is in in their talk that the book’s “story,” primarily Zafar’s story, emerges. Told in bits and pieces, it may be hard to follow, due to the author’s post-modern insistence on scrambled chronology, but it is a fascinating tale, the story, as the author informs us, “of the breaking of nations, war in the twenty-first century, marriage into the English aristocracy, and the mathematics of love.”

The mathematics of Zafar’s love is that in his case, one and one never quite made two. The love of his life has been Emily Hampton-Wyvern “a woman who had all the blessings of life, who had been born to wealth and privilege, had gone to the finest schools in the world,  a tall and slender lady possessed of a sufficient beauty and the quietly confident charm of upper-class women. Beside her, others seemed shrill.” But Emily has never fully accepted Zafar. As if ashamed of him, she doesn’t invite him to accompany her to the fancy parties she goes to, even though she’s been sleeping with him for months.

a tall and slender lady possessed of a sufficient beauty and the quietly confident charm of upper-class women. Beside her, others seemed shrill.” But Emily has never fully accepted Zafar. As if ashamed of him, she doesn’t invite him to accompany her to the fancy parties she goes to, even though she’s been sleeping with him for months.

Emily is a stand-in for England—the country which Zafar feels has never fully accepted him. He “could kill for an England” that welcomed him home after one of his trips abroad, he tells the narrator. Who is also, in a way, a stand-in, in his case for Rahman’s readers themselves. Like the narrator, we too must try to make sense of the changed and agitated Zafar, and his repeated allusions to the onerous events he has witnessed while in that cesspool of history, Afghanistan.

Rahman has been much lauded. The New York Times has called him, a “bright young star in the firmament of Indian writing.” The New Yorker’s James Wood has called In the Light of What We Know “astonishingly achieved for a first book.” I agree with these assessments, but I have one caveat in recommending this book. Rahman is not a visual writer. He never really makes us see Afghanistan, or Pakistan, or, for that matter, even some of his characters, who remain names, not people, on the page. This undeniably bright young star has frequently been compared to V.S. Naipaul. To my mind, this is a poor comparison. Yes, their subject matter is similar. But Naipaul made us not just see but virtually smell his Trinidad, his Africa, his India. Rahman ignores that classic dictum of fiction writing: show, don’t tell. He tells, not shows. This doesn’t mean the book isn’t commendable. Rahman has his own unique way of writing fiction, and what he tells in In the Light, as well as the way of telling he has chosen, is fascinating.

The Shelf: From LEQ to LES

by Phyllis Rose

FSG. 271 pp.

Phyllis Rose, who wrote the nonpareil Parallel Lives, one of my all-time favorite books, has at last come out with another book that sparkles with her own special brand of literary wit and wisdom. Parallel Lives was about the marriages of five Victorian women, four of whom were wedded—less than happily-ever-after—to men who were the giants of the literature of their time and one, the happiest, herself the literary genius in the family. With The Shelf, Rose, a longtime professor of English literature at Wesleyan, is in her element again, tossing off literary anecdotes, socking it to anointed poohbahs, firing off puns—once she even finds herself “shooting down two bards with one barb.”

Rose subtitles her new book, “Adventures in Extreme Reading,” because it’s the result of a sporting quest she set off on. She’d always wanted, she tells us, “to go where no one had gone before. To ski fresh powder in the backcountry of the Rockies. To hack through a Mexican jungle and discover a lost city… To be the first.” But unfortunately, she confesses, she is overly fond of the comforts of home, her quilt, her goose down pillow. Thus, what to do for adventure? She decides she will read her way into the unknown, read “into the pathless wastes, into thin air, with no reviews, no best-seller lists, no college curricula, no National Book Awards or Pulitzer Prizes, no ads, no publicity, not even word of mouth” to guide her. To satisfy her yearning to go where no one has gone before, she would pick a shelf in the stacks of her favorite library, the New York Society Library on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and read every book on the shelf. What would she find? Would she discover some lost masterpiece? Would some of the books, chosen so randomly, be so lethally dull she’d be wasting her time? No matter. At least, “no one in the history of the world [would have] read exactly this series of novels.”

Not that her choice of LEQ to LES was entirely random. Rather like a mountain climber who decides that the goal of a climb should be midway up, rather than to the peak, she sets her own rules for the kind of shelf to choose. She wants a shelf that contains several authors, not one filled with the output of prodigious writers like Dickens or Nordhof & Hall. She wants a shelf with a mix of contemporary and older works, and one book on the shelf has to be a classic she has not read but always meant to. Moreover, she wants her shelf to contain works by both men and women. LEQ to LES, met these requirements, and so her adventure in “Off-Road” reading, began.

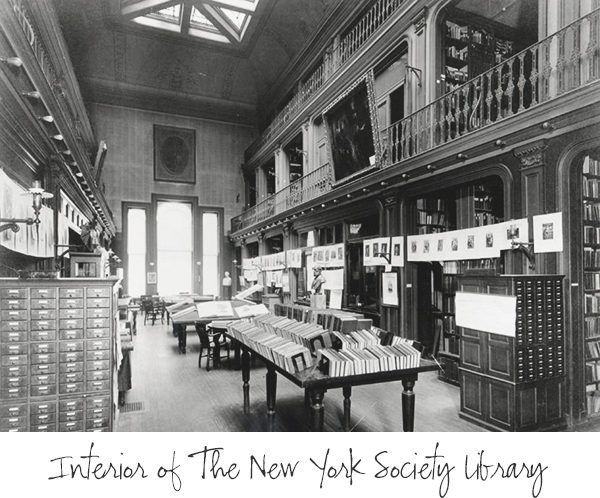

It’s a pleasure to accompany Rose as she makes her playful way through her shelf. A learning experience, too. She tackles “her” classic, Mihail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time, and finds it seriously wanting. Can it be that the translation she read was the problem? She goes searching for a translation that will make her understand why this book is considered a classic, and ends up reading four different versions of the work, including a translation done by Nabokov, who seems to explain why she’s been having a problem with the book. She’s too old to get it. It’s a work, asserts Nabokov, who first read the book as a young man and admires it despite its flaws, for young people. It’s a work that offers the young “ardent self-identification, rather than the direct result of a mature consciousness of art.”

“Take that, Lermontov,” Rose quips after reading Nabokov. “Grown-ups do not like your novel; what we like is our own remembrance of our experience of reading it when we were young.”

Rose goes on to read several books by Gaston Leroux, who wrote The Phantom of the Opera, but all of his books, except for that one, leave her cold. She tries a book by Etienne Leroux, an experimental South African writer who wrote in Afrikaans in the 1960s and was championed by Graham Greene. But she finds it beyond annoying. “Leroux had no interest in narrative. People went here and there across the estate, had this and that sighting or encounter… and never did anything.” But, scholar that she is, Rose researches the writer and learns that in his own time and in his own country, he was a literary hero of sorts because “he was trying to breathe life into a traditional and close-minded culture”. “Some books” she observes, “have an impact at the moment of their publication and for their immediate audience that they can never have again. I suspect that is the case here. Politically, South Africa has moved on, and so has literary fiction.”

There is no book on the shelf from which she does not gain important insights about literature. And she even discovers the hidden masterpiece she was longing to find. It’s a book by one Rhoda Lerman, whose Call Me Ishtar came out in 1974, the same year as Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying. Ishtar received a dazzling review in the New York Times Book Review, from a reviewer who called Lerman the female equal to Philip Roth. Her Ishtar is a raunchy retired Mother Goddess, who at a bar mitzvah “rises up in all her immortal power and… then and there, on the altar” initiates the bar mitzvah boy sexually. Yet for all the praise, Lerman’s name is virtually forgotten, and Jong’s has entered the annals of literary history. Rose takes off from this fact to deliver herself of a rollicking essay on publishing inequities, the rise of feminist literature, and the arbitrariness of literary fame.

And that’s not all, folks. There’s a lively chapter on domesticity in women’s fiction, inspired by books by Margaret Leroy and Lisa Lerner. One on detective fiction, inspired by a William Le Queux and a John Lescroart. And more.

“What I’ve learned from my experiment is respect for the whole range of literary enterprise,” Rose concludes, “for writers of all sorts, from those who make a living to those with something to say and issues to explore (not necessarily mutually exclusive), from those who aspire to create a beautiful aesthetic object, to those who want to create a clever machine… All writers seem to me in some way valiant, whether or not I put their work on the inner shelf of texts that accompany me through life.”

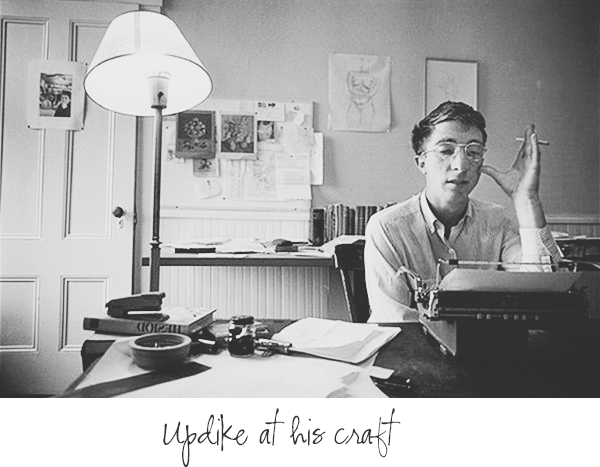

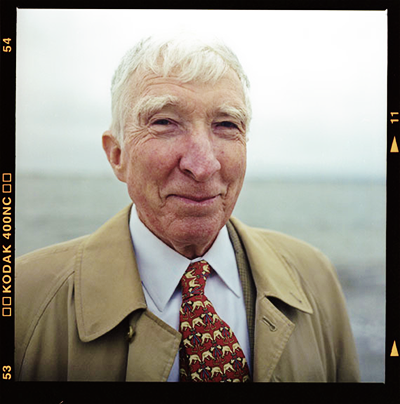

Updike

by Adam Begley

Harper. 536 pp.

Let me lay my cards on the table. I am a John Updike fangirl. Oh, I know that some of his work is superficial, some of his stories insubstantial, but I have never ceased to be awed by his dazzling prose and the way he could make the most ordinary activities of ordinary Americans, East Coast suburbanites and the denizens of middle-America, seem fascinating. Even something as ordinary as peering through a window at the weather outside. Even something as small as noticing that a wife’s nightgown is rumpled. Even hearing the piercing cry of an infant in the night. So, aware that his reputation has been sinking since his death five years ago, and that some of his last works prompted critical disdain, I share with the author of this biography the hope that there will be “a surge in his posthumous reputation.”

You wouldn’t think that reputation needed buoying up. You’d think Updike’s place in the pantheon of great American writers would be secure. After all, he wrote the commanding piece of literature about America in the second half of the twentieth century, the four books about America’s Everyman Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, Rabbit Run, Rabbit is Rich, Rabbit Redux and Rabbit at Rest, as well as the lusty Couples, the cheeky Bech books, a host of wondrous short stories, and numerous novels besides the major ones. I particularly like the Shakespeare-be-damned irreverent Gertrude and Claudius, which tells the story of Hamlet from his mother’s point of view (her son, Gertrude reluctantly admits, is a spoiled brat, cold and self-centered since childhood. Updike won every literary prize except—oddly as far as I am concerned—the Nobel, including, twice, the Pulitzer Prize, three times the prestigious National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction, and two times the National Book Award for fiction. He was chancellor of the elite American Academy of Arts and Letters, a regular on prize committees, and a constant supporter of gifted younger authors, making their work known through his enthusiastic reviews in the New Yorker.

Yet his very productivity and eminence earned him the hostility of rival novelists, like Gore Vidal, who said of him that he “describes to no purpose,” and David Foster Wallace, who dismissed him as “a penis with a thesaurus,” as well as of august critics like James Wood, who snipped, “It seems to be easier for John Updike to stifle a yawn than to refrain from writing a book,” and John Aldridge, who in the New York Herald Tribune opined, “He does not have an interesting mind. He does not possess remarkable narrative gifts or a distinguished style.”

Whoa! Who but John Updike could have written this sentence, which I just picked at random after leafing through one of his books: “While our baby cooed in her white, screened crib, and the evening traffic whished north on the West Side Highway. And Manhattan at my back cooled like a stone, and my young wife fussed softly in our triangular kitchen at one of the meals that, by the undeservable grace of marriage, regularly appeared, I would read.”

There’s an entire story in that sentence—the new baby, the chore-laden wife, the self-absorbed husband pursuing his own pleasure, in this case, reading. And in a way, there’s a movie here, too. Because we see the scene. Updike’s style, unique to him and certainly distinguished, combines the artist’s eye for visual detail and the storyteller’s drive to form a narrative, implicit here in the sentence’s air of melancholy. For as we all know, melancholy can result from or precipitate conflict and drama.

Begley’s Updike is an examination of Updike’s life and of how the writer repeatedly used shards of that life to create his stories and novels. “His stories are conspicuously autobiographical,” Begley writes. And, despite the remorse he sometimes felt when friends complained they were recognizable in his work, he held to the precept that “nothing in fiction rings quite as true as the truth, slightly arranged.”

Interviewing scores of people who knew the author (though not his second wife, who refused to cooperate), and giving close readings to the writer’s own words, Begley shows us how Updike’s original ambition of becoming a graphic artist colored his work as a writer of fiction. What catches the eye in Updike’s fiction is, from the start, Begley says, his “telling use of minute, convincing detail… and bursts of clear-eyed description.”

Begley shows us, among other things, how different Updike was from the easy-going cheerful persona he presented to the public, how frightened he was all his life about aging and death, and how deeply wounded he was by criticism. He tells us how strained the relationship was between Updike and his children by his first wife after he married the second. He tells us who the author’s friends were, and who the friends who became enemies were. And throughout the book one feels the biographer’s appreciation of Updike’s work and his sympathy for the hardworking writer behind the creations.

“It’s possible,” Begley writes, “that I was programmed to like him.” His father, Louis Begley, himself a major novelist, was a classmate of Updike’s at Harvard and according to Begley family legend, Updike was the first person to elicit a laugh from infant Adam. Grown up, and become a literary critic himself, Begley became an admirer of the writer’s gorgeous style, and his moving depictions of American life.

In his Updike, he has given us about as full a picture of this prodigious author who never tired of creativity as we are likely to get, and it is simply splendid.

Authorisms

by Paul Dickson

Bloomsbury. 226 pp.

Paul Dickson, who has written some dozen books about words, including Words From the White House and Slang, has now come out with this amusing anthology of words made up by authors. Some were invented by famous authors, like Shakespeare, who coined hundreds of new words that we still use today including “critical,” (oh, yes, he was a writer—he knew from critics) “bedazzled,” and “hurry.” Some were invented by less famous authors of classic works or by contemporary writers, some of whose words have passed into common parlance, some of which bombed out—or were subjected to “verbicide,” a word invented by C.S. Lewis to mean the killing off of a word.

Did you know, for example, that the word, “feminist,” was coined by Alexandre Dumas back in 1873, when French women were first beginning to assert that they were equal to men? That “the almighty dollar,” was a phrase coined by Washington Irving way back in an 1836 story? That “Master of the Universe,” which I thought was Tom Wolfe’s creation, arose, actually, from the imagination of John Dryden. Or that “friending,” that irritating word popularized by Facebook, and which I thought was made up by Mark Zuckerberg, was actually another creation of Shakespeare’s, which he featured in Hamlet?

Doing “the beast with two backs” was Shakespeare’s, too, his discreet coinage for you-know-what. But “bardolatry” is a word George Bernard Shaw made up to toss at people who blindly idolized that playwright. “Videot,” one of my favorites in the book, is sportswriter Red Smith’s word for people who will watch anything at all, however dumb, on their TV screens. “Doublethink” was George Orwell’s. We owe terming economics “the dismal science” to Thomas Carlyle, and speaking of economics, “billionaire” was super-judge Oliver Wendell Holme’s creation to denote the rich baddies of his era. With the rich getting richer all over the world today, some writers have begun calling the rich baddies of our time “trillionaires,” and I hear it’ll soon be more correct to say “quadrillionaires.”

Besides successful made-up words, Authorisms also offers lots of failures, words that were made up but fizzled out, going nowhere. Like Virginia Woolf’s “vagulous,” meaning vague or wandering, which never appeared in print except in her own works, and “alogotransophobia,” the fear of being stuck on public transportation without something to read. It was created by a committee of three Bostonians to address the absence of such a necessary word in their book loving public transportation-challenged city. Then, for folks lucky enough to have something to read, the humorist Franklin P. Adams invented the word, “unlaydownable,” for a book so good one just can’t stop reading it, which due to the popularity of a word coined slightly later by Raymond Chandler, “unputdownable,” fell victim to verbicide.

James Fenimore Cooper wanted to call female Americans “Americanesses,” which didn’t go over big even in the 18th century, well before we all learned not to refer to those helpers on airplanes as hostesses, or the ones in restaurants as waitresses, or the female folk on stage as actresses. My favorite among failed words? It’s “smirt,” a word that novelist James Branch Cabell wanted us to start using as an expletive: “If it isn’t obscene,” he wrote, “it certainly sounds like it.”

Light-hearted, informative, and never the least bit vagulous, Dickson gives us all of these and more. You can easily while away an afternoon going through Authorisms from A to Z, and come out with, if not an enriched vocabulary, at least a fresh stock of verbivoria (dare I say logovoria?) with which to entertain some of your friendlings, that is, people you like friending.

The Arsonist

by Sue Miller

Alfred A. Knopf. 304 pp.

Eons ago, I was the first reviewer to call attention to a debut novelist named Sue Miller in the pages of a major publication. I wrote a review of this unknown author’s The Good Mother that appeared on the front page of the New York Times Book Review. Astonished by her talent, I went out on a limb and wrote, “Every once in a while, a first novelist rockets into the literary atmosphere with a novel so accomplished that it shatters the common assumption that for a writer to have mastery, he or she must serve a long, auspicious apprenticeship.” Then, in love with my image, I went on to play with it, saying, “This novel arrives gleaming, ticking, and we are filled with awe.”

I’m pleased for having detected this author’s talent so early, and pleased that Miller went on to write a good many fine books after that first one. In The Arsonist, her tenth book, she once again delivers a novel that, engrossing and rich, is a showcase for her unique ability to get into the nitty-grittys of familial and romantic relationships.

“Maybe by home,” thinks one of the characters in The Arsonist, the aging, Alzheimer’s-afflicted Alfie Rowley, “he meant the time when he felt whole, when he felt like himself.” Alfie, whose disease is eroding not just his memory but his personality, has literally gotten lost.  But each of the principal characters in The Arsonist is figuratively lost, trying to find their home, in the sense of the place in which they can feel most whole and most like themselves.

But each of the principal characters in The Arsonist is figuratively lost, trying to find their home, in the sense of the place in which they can feel most whole and most like themselves.

There’s Frankie Rowley, one of Alfie’s two daughters, who has just returned for a visit to her parents at their summer house in Pomeroy, New Hampshire, after years of living in Africa doing aid work, going from one desperate country to another, one transient love affair to another. She’d loved her work. “The extremity of it, the absorption of it, the fatigue, the high.” But she’s begun to feel burnt out. Can she make a different life, a home, for herself back here in the States?

Her mother, Sylvia, has been ambivalent about her husband for years, has resented him for disparaging her career as a teacher, for preening himself as a scholar, for the way he behaved with their children when they were little. “He wasn’t really interested in them in any steady way—though of course, being Alfie, he read Piaget, Erikson, Aries, Winnicott… He had never changed a diaper.” Sylvia’s not sure if she will feel whole and like herself if she has to devote her waning years to Alfie’s care.

Then there’s Bud Jacobs, a D.C. newspaper man, who has just given up big time journalism to buy the local weekly in the Rowleys’ hometown, where he reports on school plays and team games instead of supreme court decisions. When Frankie tells him she has been suffering from burnout in her work in Africa, Bud allows that he’s burnt out, too. “With real life,” he says.

Frankie and Bud will fall in love and have a hot affair with a potential for permanence that frightens Frankie. Bud will try to put down roots in Pomeroy, Frankie or no Frankie. And at one point, Sylvia will counsel her daughter, “Your life made all this relationship stuff seem dispensable.”

It is, of course, “all this relationship stuff” at which Miller excels. Mothers and daughters. Fathers and children. Sisters. Lovers. Wives and husbands. But there’s more to The Arsonist than the subtleties of relationships. There’s a mystery in the book, too, one that revolves around a series of fires that have been burning down the homes of numerous of the town’s summer residents. With consummate delicacy Miller explores the troubling split that divides many a summer resort, the great divide between the haves, the well-to-do summer people who briefly inhabit second homes, and the less affluent locals who cook and clean for the summer folk, who sell them their groceries, mow their lawns, fill their gas tanks, and hide their resentment behind an artful affability.

I won’t tell you who set the fires. For one thing, like Frankie herself, I’m not even sure. Just as I’m not sure whether Frankie, Sylvia and Bud are making the right choices for themselves at book’s end. But neither are they. One of the many things I found intriguing about this novel is the way scene after scene unfolds—and reads&mdashl;like life itself. With all its big questions, and all our small, yearning, maybe-right-maybe-wrong answers.

The Silkworm

by Robert Galbraith (a.k.a J.K. Rowling)

Mulholland Books/Little Brown & Co. 455 pp.

I’m sure you’ve read enough about this latest Cormoran Strike detective novel not to need another admiring review of it. But I’ll put my own two cents in here anyway, just for the record. Rowling is a master storyteller. Strike is a dynamite character. He’s easy to fall in love with. For his courage—wounded in Afghanistan, he’s lost a leg, has a prosthesis, is in constant pain, but bears it all bravely as he hobbles around London searching out villainy. For his perspicacity—in the fashion typical of P.I. books, he’s way smarter than the police. For his kind heart—though he’s broke and has sworn he’ll only take on only lucrative cases, he can’t help himself from agreeing to help out a poor widow. For his wry sense of humor, and his broken heart, and his cynical views on life at the top. He’s such an engaging character that he may well be the next Sherlock Holmes, the next literary detective whose company readers enjoy as much as they enjoy the mysteries he solves.

This is Rowling’s second Cormoran Strike book. There will be seven altogether, the same number of books as Harry Potter got. This one is particularly fun for those of us who love books because its setting is the world of publishing, a world of secret deals, replete with pushy agents, tricky editors, greedy publishers, egotistic best-selling authors and resentful midlist ones, a world whose shenanigans Rowling knows well.

The Silkworm is the summer book you’ll want if you’re taking a plane or a train, or just trying to ignore the heat. Unlike the Harry Potter books, there’s no magic per se in absorbing, witty and suspenseful Silkworm—and yet, with its ability to block out surroundings and annoyances, make them altogether disappear, the book is in itself magic.

To enter to win your book of choice,

comment below by answering the question:

Which of these books do you want to read and why?

1 FOF will win. (See official rules, here.) Contest closes July 24, 2013 at midnight E.S.T. Contest limited to residents of the continental U.S.

18 Responses to “{Book Critic & Giveaway} Summer Picks from Linda Wolfe”

Sue Watson says:

I would like to read the Silkworm. I like a good detective novel, especially knowing the lead character is looking forward to a few more books.

Sue Miller says:

J K Rowling- I love all her books and am looking forward to this one too!

Alice E. Dehne says:

Silkworm by Robert Galbraith sounds like it would be a great read. I love a good book with suspense.

Beatrice P says:

I would love to read, In the Light of what we know. The author’s life seems interesting and engaging.

DawnMarie Helin says:

I am truely torn between The Shelf and The Arsonist. Both appear to be rich, without being lecturing. I enjoy both fiction and nonfiction, but in either case, if I feel as though the author is lecturing me on the characters, I’m put off and can’t move forward. I want to discover the characters or the subject as I read along, not be forced into a position one way or the other.

Linda DeBlois says:

I read the first book with Cormoran Strike. It was wonderful. I am one-third of the way thru The Silkworm and don’t think it is as good as the her first one. J.K. Rowing that is. I hope I am wrong and this one turn out better than her first.

Toni Hughes says:

I want to read all of them. All. Of. Them.

wetc87 says:

The Silkworm — I’m currently halfway thru ‘The Cuckoo’s Calling’ and have already fallen in love with Strike. Can’t wait to finish and start the next installment in the series.

Katie says:

Either Authorisms or Silkworm because I love a good mystery and Rowling

Bibliophile says:

It’s wonderful to see Linda bucking the summer beach book trend for such rich intellectual fare, casting her critical intelligence and effortlessly insightful style on Phyllis Rose’s bookshelf adventures and Adam Begley’s “Updike.” As a verbivore, though, I think I’d find “Authorisms” most irresistible, if not “unputdownable.”

My only quibble: we can’t quite blame Shakespeare for the rise of “friending,” since he used it as a noun, not a verb. When Hamlet tells Horatio and Marcellus that he will “express his love and friending to you,” he’s employing an obscure variant for “friendship,” not the present participle of an abbreviated “befriend.”

S'Linda wolfe says:

Thank you for this arcane bit of info. Most interesting!y

Debby Stock Kiefer says:

Authorisms is the perfect book among these for a household populated by two journalists, one of whom is a news addict and history buff. Unlike my husband, I turn to fiction for escape. But we both are passionate about language. We could read before we could tie our shoes. He learned to read on his father’s lap, from the daily paper. My mother and brother taught me, probably from library books. Now, our dates often include a stop at the nearest library.

Linda Wolfe says:

Thanks, Debby. I share your enthusiasm for words!

Jim Wintner says:

I will definitely be reading Adam Begley’s Updike bio. I am a huge fan of Updike, but his personal life is hidden from me (unlike Norman Mailer who I am re-reading at the moment). Although he may not be the smartest or the best stylist, his accomplishment in creating, and writing about, Harry Angstrom (Rabbit… I hope I have his name right) is simply unsurpassed in describing and illuminating the beliefs and challenges of one American everyman. Such that I have proposed that along with Babbit, the Rabbit books (Rabbit/Babbit…Babbit/Rabbit… hmmmmm!) book end the mind of the American everyman and teach us many profound truths about the American character and “religion”.

I might add, that I asked Updike – at a reading – about this seeming coincidence. He responded that he had not read Babbit until after the second Rabbit book. He said he had not read it earlier because he was certain that Sinclair Lewis did not love Babbit (and it has always been clear that Updike loves Rabbit), but of course he did. So there you are. Perfect symmetry…. pure happenstance.

jw

Jim Wintner says:

I wanted to clarify that Babbit and Rabbit are the everyman of the 20th C. Not sure who that is for the 21st.

jw

Linda Wolfe says:

Thanks, Jim. Do reread some of the stories. And one quiet day try Gertrude and Claudius. It’s really fun.

Rebecca Schull says:

I’d like to read the j.k.rowling book because I’ve not read any of the Harry potters and feel that I’ve separated myself from the general reading public by this lapse and maybe I can redeem myself and have some fun at the same time.

I very much enjoyed your list and your comments, particularly about the great john Updike.