The publishers’ catalogs I peruse to see what’s coming up for the next season promised a veritable cornucopia of literary treats for the fall. Because I was about to set off for an extended stay in England and wanted to travel light, I chose a number of titles, obtained advance electronic galleys, and ended up toting a shelf full of upcoming books in my Kindle. They made for terrific travel companions as I sightsaw around London and reconnected with old friends in Oxford.

Here are the books that were my favorites.

Want to win a copy of one of these books? To enter to win, comment below by answering the question: Which of these books do you want to read and why?

FOF award-winning author, Linda Wolfe, has published eleven books and has contributed to numerous publications including New York Magazine, The New York Times, and served the board of the National Book Critics Circle for many years.

The Bone Clock

by David Mitchell

Random House. 624 pp.

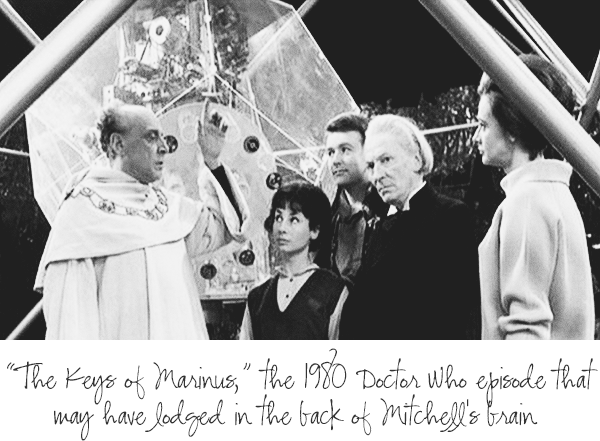

Am I the only American book critic to detect a direct connection between David Mitchell and a story that was on the Dr. Who TV series way back in the nineteen-sixties? Mitchell wasn’t even born when the story first aired. But in 1980, when he was a pre-teen, a novelization of the classic early show, called The Keys of Marinus, was published. Interestingly, some of the action in The Keys of Marinus was filmed on Britain’s Isle of Sheppey. Is it too far-fetched of me to speculate that the eleven-year-old Mitchell—the perfect age for gobbling up sci-fi novels—read the novelization and learned about the old film, after which, for the rest of his life, there lodged somewhere in the back of his brain the intriguing-sounding names of Marinus and of the Isle of Sheppey? Marinus is a planet in the Dr. Who story, a character in some of Mitchell’s books; the Isle of Sheppey is the place where some of the most important action in Mitchell’s new book, The Bone Clocks, takes place. Okay, so what if I my idea is a bit fanciful? When it comes to David Mitchell, no one can come up with ideas more far-fetched than his own.

The new book contains six sections covering the years between 1984 and 2043, and features several thoroughly believable characters who speak in Mitchell’s slangy captivating voice. There’s Holly Sykes, a teenage runaway; Hugo Lamb, a devious Cambridge student with whom she has an affair; Ed Brubeck, a war reporter she eventually marries; and Crispin Hershey, a friend of hers who was once a bestselling novelist but has now fallen into the sorry pits of the midlist. There are also fantastical figures who enter Holly’s life. Some are immortal by nature, like kindly Dr. Marinus, who turns out to be hundreds of years old, others are immortal by virtue of decanting and drinking the blood of young victims, like the malevolent Imaculeé Constantin.

Ya’ gotta love sci-fi to get with this book, which ultimately turns into a holy war between Good and Evil, between the better angels of our nature and the Satanic ones. Yeah, okay, there’s literary tradition here, John Milton and all that. But the problem with Mitchell’s holy war is that his devolves into a cartoon. The battle between the good guys and the bad guys takes place in The Chapel of the Dusk of the Blind Cathar, which is actually “the body of a living being,” where the Cathar can flee from an icon of himself into “the floors, walls, and ceiling.” Marinus’s side is losing. He’s even killed—at least until he can get himself a new human in which to reconstitute himself. “Seeing my dead body against the wall,” Marinus tells us, his opponents figure “no psychcoteric can now attack them, and their red shield flickers out.” But, “They’ll pay for this mistake,” he thinks. (Yes, he can think, even though he’s been “killed.”) “Incorporeally, I pour psychovoltage into a neurobolas and kinetic it at our assailants.” But then the Blind Cathar “evaporates” one of Marinus’s companions “with a short, sharp psychobolt.” The battle’s over. “They’ll kill Holly,’” Marinus fears, “or try to decant her,” whereupon the Blind Cathar “psycholocates the soul” of another of his companions.

And so on. It was all so thoroughly silly that I kept asking myself, why am I reading this?” But read it I did. Because Mitchell’s style is so compelling that you want to stay within his story forever—except when you come to your senses and ask again, “Why am I reading this nonsense?”

I loved Cloud Atlas, where the science fiction worked splendidly. It just doesn’t here. And yet Holly and Ed, Hugo and Crispin are tremendously engaging. The problem with The Bone Clocks is the ludicrous prepubescent plot.

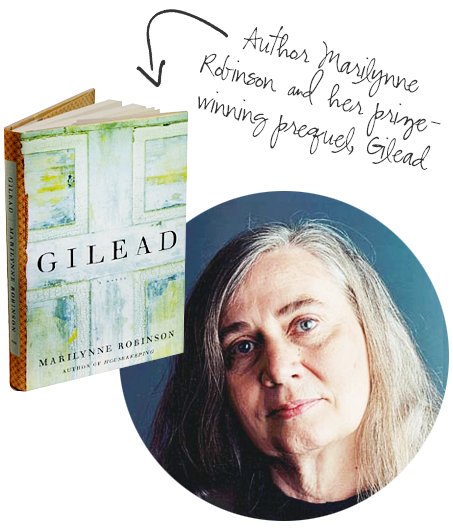

Lila

by Marilynne Robinson

FSG. TK pp.

In her prize-winning novel Gilead, where she introduced the thoughtful Reverend Ames, we learned that when he was already elderly the Congregationalist minister had married a much younger wife. But who was she? And why did she marry an old man? Lila is the story of that woman. And it is arguably the best book Robinson has ever done.

Lila is a child about four years old who no one claims. “Nobody gonna want you around,” the people with whom she’s living shout at her, and push her out of their house. She sits fearful, feverish, and weeping on the doorstoop. “And after a while night came. The people inside fought themselves quiet, and it was night for a long time… she was nearly sleeping when Doll came up the path and found her there like that, miserable as could be, and took her up in her arms and wrapped her into her shawl.”

Lila doesn’t know who Doll is, she’s just another of the brawling inhabitants of the house out of which she’s been thrown. Indeed, she’s one of the worst of the inhabitants, the tiny girl thinks, someone who was always rubbing and scrubbing at her face and pulling a hurtful comb through her tangled hair. Doll is just a name to her. Which is more than she can say for herself, as no one’s ever called her by a name, just shouted, “You!” at her. But on that terrifying night when Doll scoops the abandoned child into her shawl and says, “Well, we got no place to go. Where we gonna go?” the girl, soon-to be-named Lila, lets herself be cuddled and stolen away from the house.

Thus begins an odyssey through the farms and fields of 1920s Iowa, where Lila and Doll join up with a few other farm workers and live from hand to mouth, doing field work, feeding on corn stolen from the fields and scraps begged from kindly farmers. When the drought comes, the work dries up, and the little group often goes hungry. But the destitute migrant farm workers are a kind of family for the familyless child, and Doll is a kind of mother for the motherless child, who cares for Lila even when their group, desperate to have fewer mouths to feed, excludes them. The pair struggles on alone in poverty and misery, although there’s one good year when Doll finds town work and sends Lila to school. Then Doll is hunted down—I’ll skip the hows and whys to spare you spoilers—and Lila ends up in a St. Louis whorehouse. She’s a broken spirit, angry, suspicious, hating her present, mourning her past, her only legacy from Doll a sharp hunting knife, which she treasures as a memento but also intends to use on anyone who tries to harm her.

How Ames manages to tame this feral child—well, feral young woman by now—to bring her to God, and to himself as a wife is the haunting exquisite tale told in Lila.

This book is a winner. And will no doubt win many of the prestigious literary prizes of the year.

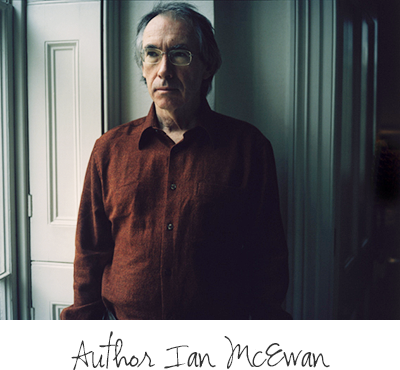

The Children Act

by Ian McEwan

Talese/Doubleday. TK pages

Even a flawed book by Ian McEwan is a turn-on for me. Even when this guy is not at the top of his game, you get more bangs for your buck when reading him than you get from 99% of the competition. His voice is as sweet and smooth as crème fraiche, his enlightenment Voltarian, his concerns always up-to-the-minute. In The Children Act, he writes in the first person as a woman—something very few male writers are able to pull off successfully—and makes his creation, a High Court judge in Britain’s Family Proceedings Court, entirely believable.

Fiona, the judge, is fair and rational. “She believed she brought reasonableness to hopeless situations… she took it as a significant marker in civilization’s progress to fix in the statutes [read in England’s Children Act] the child’s needs above the parents.” But her days are filled with mothers and fathers “in vicious combat with the one they once loved, and boys and girls huddling together while the gods above them fought to the last minute from the Family Proceedings Court to the High Court to the Court of Appeals. Having to adjudicate amidst all this unhappiness is exhausting, and in time one case in particular begins to gnaw at her, making her numb, unable to talk to people, even to her beloved husband, as if “some part of her had gone cold.”

The case is that of Matthew and Mark, conjoined twins, one of whom will die if the court rules to sever the babies’ connection. But both will die eventually if they are not separated. Fiona rules in favor of the separation, but afterward feels “a blind and purposeless nullity” about life. “A microscopic egg had failed to divide… a gene transcribed in error, an enzyme recipe skewed, a chemical bond severed. Which only brought into relief healthy, perfectly formed life, equally contingent, equally without purpose. Blind luck to arrive in the world with your properly formed parts in the right place, to be born to parents who were loving, not cruel, or to escape by geographical or social accident war or  poverty.”

poverty.”

She becomes so depressed that “not having a body, floating free of physical constraint, would have suited her best.” Her husband, Jack, is dismayed by her new remoteness. “Where is the sex?” he asks. “I don’t keep a record,” she snaps. Unwilling to live with a woman who has grown so distant, Jack tells her he no longer wants their comfortable and correct life together. He’s still in love with Fiona, he insists, but he wants, he needs, ecstasy. And if she won’t help them reignite their relationship, he intends to leave her.

Fiona is too proud to plead with Jack to get him to stay. She lets him leave, despite her fears of being a woman alone. “It was not contempt and ostracism she feared, as in the novels of Flaubert and Tolstoy, but pity. To be the object of general pity was also a form of social death. The nineteenth century was closer than most women thought.”

The Children Act isn’t one of McEwan’s triumphs. The plot—which involves how Fiona manages after Jack departs, and her uncharacteristic behavior in deciding another case—is thin, and Fiona herself is the only character in the book who is fully fleshed out. But it’s precisely because of the way she’s fleshed out that I admire this book. In his heroine, McEwan gives us a woman whose thought process is utterly fascinating. There are many contemporary novels with a central female character who holds a position of prestige or power. But generally we see only their actions, rarely the working of their minds, get no firm clues as to how they achieved their important positions. Fiona Maye is a female character whose very thoughts, even more than her actions, are exciting—and a real joy to read.

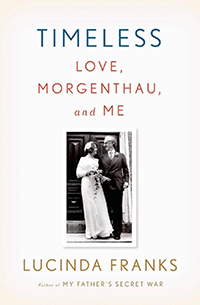

Timeless

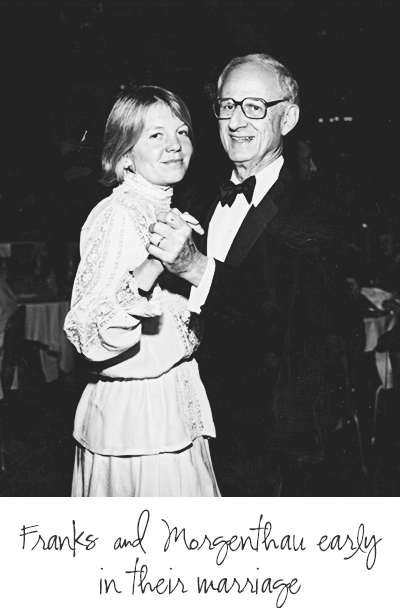

by Lucinda Franks

FSG. 379 pp.

If you like a good love story (and who doesn’t?), Lucinda Franks’ Timeless will knock your socks off. It’s the story of an improbable romance, a coming together of two people who seem utterly mismatched in every way. Franks, a Pulitzer-prizewinning journalist, was twenty-six years old when she started dating Morgenthau, the District Attorney of New York, who, at fifty-three, was nearly three decades older than she was. He was a widower, with five children, including two daughters around her age. She was single and childless. He was a diffident, buttoned-up patrician, private to his very core. She was a bohemian, a let-it-all-hang-out hippie.  They were, Franks writes in this intimate and insightful love story, “as suited to each other as a giraffe to a baby kangaroo.” Who’d-a-thunk they’d marry and still be married thirty-nine years later, and that nowadays, with Franks at sixty-five and Morgenthau at ninety-two, they’d be as happy, possibly happier than, the day they were wed.

They were, Franks writes in this intimate and insightful love story, “as suited to each other as a giraffe to a baby kangaroo.” Who’d-a-thunk they’d marry and still be married thirty-nine years later, and that nowadays, with Franks at sixty-five and Morgenthau at ninety-two, they’d be as happy, possibly happier than, the day they were wed.

Not that the marriage didn’t suffer from anger and anguish, battles and bruises, hurt feelings and differing modes of seeing the world. In an early scene, Franks and Morgenthau are in an airplane flying over the Alps. “The universe is so vast,” Franks says, “and we are so little. Sometimes I think, ‘What are we, anyway?’ Have you ever wondered, ‘Hey, what am I?’” “This is a big plane, isn’t it,” Morgenthau responds. “It’s a McDonnell Douglas DC-10. Three engines.”

The scene becomes almost an iconic one of their marriage, as, like so many women who need emotional exchange married to men who won’t—or just don’t know how to—offer it, Franks struggles with her husband’s almost impenetrable defenses against the display of feelings. She recounts many of his famous cases—his pursuits of the Mafia, his triumphant fight against New York’s death penalty law, his efforts to return art stolen by the Nazis to their rightful owners, and many more. But essentially Timeless is a book about marriage, and how devotion can keep one going.

Over the years, Franks keeps bugging her husband to be more revelatory, and he keeps resisting her efforts. Eventually she discovers the roots of his “habit of removing himself from an emotional argument” in the PTSD he suffered after World War II. She helps him to overcome it, and also learns to read him better, to understand “that somewhere you expect me to act not on what you say, but on what you don’t.” In the end, still as much in love with her husband as she was when they had their very first passionate sexual encounter, she concludes that love can simply look different to the partners who engage in it. “To me,” she writes, “love was about showing and telling.” To her husband, “it resided in doing,” like serving her blueberries in bed or making a call on her behalf. As for him, “What he thrived on was quiet affirmation, gentle caring… being there for him when he needed you.”

It must have taken great courage on the part of both Franks and Morgenthau for this book to see the light of day. On her part for writing about their marriage with utter and incandescent honesty, and on his for respecting his wife’s talent so much that he agreed to and even assisted her in invading his lifelong habit of privacy.

It makes for a terrific book. I doubt that the wife of any other major political figure of the Twentieth Century has written a memoir that is as personal, as engaging, or as splendidly told as this one.

The Visitors

by Sally Beauman

Harper. 526 pp.

Hidden tunnels. A three-thousand-year-old tomb. Secrets and skullduggery. Gold, gold, and more gold. In The Visitors, Sally Beauman tells the story of Lucy Payne, a ten-year-old British girl recovering from typhoid, the disease that has just killed her mother, whose preoccupied father sends her to regain her health in the sunny climes of Egypt. She’s in the care of a guardian, and the pair just happens to get to Egypt at the time that famous archaeologist, Howard Carter, afraid he is about to lose the funding of his patron, Lord Carnavon, is desperately searching for the tomb of King Tuthankamen. Child and caretaker make friends with an American archaeologist involved with the search, his wife, and his little daughter, Frances. Lucy and Frances become fast friends, play together among the desert excavation sites, and are in on all the gossip and intrigue that surrounds the search for and discovery of King Tut’s tomb.

So far, so good. If you like historical novels, this one is fine when it recounts this world-shaking event of the 1920s and mixes famous figures like Carter and Carnavon along with imagined ones like Lucy and Frances. Unfortunately, however, the tale keeps going, giving us snippets of Lucy’s life as she grows up, gains a stepmother, gets married, gets divorced, moves into various homes, becomes an artist, fights off a documentary film maker who wants to know if she knew whether Carter had snuck into the tomb before he announced his discovery to the world. (She doesn’t.) Lucy grows older and older, her life is essentially uneventful, and characters who seemed important earlier in the book are swiftly killed off by the author, who seems to have lost her direction once she’s out of Egypt.

I say read this one if, like me, you’re fascinated by those historic discoveries in Egypt, but expect to be let down once you’re back in England.

The Betrayers

by David Bezmozgis

Little Brown. 240 pp.

Bezmozgis hasn’t gotten the attention he deserves. A Canadian whose family emigrated from Russia in 1978, he is the author of the stunning novel, The Free World. That book was set in Rome, where the first Jews allowed to leave the Soviet Union had to wait, stateless, until they obtained the visas necessary for gaining entry to the United States or Canada. Epic in scope, it told the stories of an entire family of emigrés, the Krasnanskys, from the elderly grandparents to their sons and daughters-in-law to their grandchildren, as well as those of assorted acquaintances.

Bezmozgis’s new book is smaller, the story of just one man. He’s Baruch Kotler, a Soviet dissident who was sentenced to many years in a harsh prison camp. Shortly before his incarceration, Kotler had married Miriam, a woman who agitated unceasingly for his release. When finally that release came and the pair reunited in Israel, they were more or less strangers to one another. Still, they stayed together, had two children, and became symbols in their new land of the power of never giving up—a particularly potent idea in beleaguered Israel.

Unfortunately, however, Kotler, who is now an honored, even adulated Israeli politician, has had a midlife crisis, a yearning for passion, and has started an affair with an aide many years his junior. Hoping to spare his family, Kotler tries to keep his relationship with the young woman secret. But he has taken unpopular stands regarding the West Bank, and when his political opponents get photographic evidence of the love affair, they release it to the press. Kotler is disgraced, and flees to Yalta with his aide.

There, accidentally, he crosses paths with Chaim Tankilevich, the man who betrayed him in Russia all those years ago. Tankilevich feels he has paid for his actions. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, his betrayal of the heroic Kotler has made him scorned and reviled by fellow Jews wherever he goes. An outcast, he is destitute, filled with self-hatred as well as a surly fury directed at everyone around him. And Kotler, who is now a betrayer of sorts himself, must decide whether and how to be revenged on him.

Boiling with suspense and dramatic confrontations, all spiced with pungent moral complexities, this one’s a great read!

To enter to win your book of choice,

comment below by answering the question:

Which of these books do you want to

read and why?

1 FOF will win. (See official rules, here.) Contest closes October 23, 2014 at midnight E.S.T. Contest limited to residents of the continental U.S.

25 Responses to “{Book Critic & Giveaway} Fall 2014: A Cornucopia of Treats”

Cynthia Richardson says:

I would like to read The Visitors. Why? OMG – “Hidden tunnels. A three-thousand-year-old tomb. Secrets and skullduggery”. This is my favorite type of story!!

Maren says:

Sounds like they all have something to recommend them, but I think I’d most prefer The Children Act.

Charlene Vos says:

Lila seems very interesting to me. As a foster parent I know the hurt and sometimes anger that an abandoned child projects in so many ways.

The Sunday Scoop for 10/12/14 – finding giveaways you want to enter says:

[…] FAB OVER FIFTY – book giveaway, your choice out of 6 current […]

Christine Norman says:

Lila sounds like a very heart touching novel.

Alison McManus says:

My first choice out of this fabulous feast would be “The Children Act”…I love anything by Ian McEwan! His characters are always so believable no matter what unbelievable situations they are in…I would love to nestle down with a cuppa tea…a tin of biscuits….and this new release!

Nikki Kreymer says:

My book choice would be “The Betrayers” because I am unfamiliar with the author and the plot description appeals to a universal curiosity. Who doesn’t wonder what they would do or say if they had the chance to confront their tormentors? Would we enact the rehearsed speech and actions buried deep in our memories or would in-your-face personal release something else? What do years of life experiences do to a desire for justice or revenge? This book appeals to victims of betrayal whether bullying or theft or murder or finances or love!

Bibliophile says:

Sign me up for “The Children Act”! McEwan’s enlightenment is Voltairean? Linda had me at “creme fraiche”!

Roxanne says:

Timeless by Lucinda Franks sounds very interesting. Memoirs are one of my favorite genres. The couple’s very large difference in age is only the start of the relationship that sounds like it went through many changes over the years.

Sandra says:

I want to read Timeless, by Lucinda Franks. I enjoy a good memoir, and when I was growing up in New York City, Robert Morgenthau was a major political figure, who always interested me. Also, since Franks is a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, I assume her writing is excellent.

Ruthie B says:

Lila sounds excellent & I’m going to go get Gilead to read too!

Debbi F says:

“Timeless” by Lucinda Franks is my choice to read first of the interesting group described. I particularly like the idea of reading a memoir of such an unusual and category setting couple that have sustained their marriage for so many years…hope my name is chosen for the prize.

Sacha Schroeder says:

I would like to read The Children Act because it looks a good read and sounds interesting,

Deborah Blake says:

I would love to read “Lila” -she seems so brave, I want to learn more about how she survives.

Eugenie says:

I want to read The Bone Clock. I’ve read all of David Mitchell’s other books. I especially enjoyed The Cloud Atlas and want to experience his storytelling again.

Linda Flack says:

Absolutely, The Betrayers! I’ve always been grateful to my grandparents for coming to this country. Don’t know if I could have done it. Love reading books about those who made the extremely tough journey.

Susan says:

THE CHILDREN ACT by Ian McEwan!!! I am a licensed clinical social worker and always fascinated about what drives human behavior. Having worked closely with the family court system by providing therapeutic services for parents involved in abuse and/or neglect cases, I recognize the importance of boundaries and balance. I would love to read this book.

eddyrobey says:

The Betrayers, because forgiveness is a treasure I hope to find in it.

susan beamon says:

I would like to read THE VISITORS by Sally Beauman. I like stories set in Egypt during the great archaeological treasure hunt.

Mary G says:

I’d very much like to read “Timeless.” I’m a fan of memoirs, and this sounds like a fascinating and emotionally revealing one.

jean olaughlin says:

I would love to read Timeless by Lucinda Franks. I think it sounds like a lovely read. Opposites attract.

Tricia Douglas says:

THE VISITORS sounds like something magical and mysterious. I’ve always wanted to visit the pyramids and see a bit of history at it’s best. If not traveling, reading is the next best thing. Keeping my fingers crossed.

Kathy says:

“LILA” pulls at my heart strings. I have been a foster parent and have seen many hurt damaged children in my life. I know it is hard for children from poverty and a poor start to find acceptance and a means of making something of themselves. The synopsis caught my attention more than any of the others.

kgritts says:

I would like to read Lila. Both reviews I’ve read have given it high marks and it looks intriguing.

Jane Immel says:

I would love to read The Children Act…this is the second review I’ve read of it and it really sounds interesting…