I’ll never forget what one of my best friends, a valiant woman who had fought breast cancer for years, said when her doctors told her one July a few years ago that this was It, they’d exhausted their possibilities for her and she had only six months or so to live. Rachel, who was given to ironic statements, smiled her gorgeous wry smile and said,

“Thank God! At least I won’t have send out Christmas cards this year!”

I think about this a lot at this time of year when there’s just too damn much to do, gifts that have to be selected and wrapped, tips that have to be doled out, charitable contributions that have to be made, food that has to be bought in uncommonly large quantities and baked or boiled, broiled or brandied, and of course the stacks of Christmas cards that have to be written and taken to the bloody Post Office where the lines are so long I feel like I should have brought a folding chair with me. Given all this, the last thing I want to do is tackle a long book. But after a day of knocking myself out with chores, reading is how I relax at night. So every year at this time, I find myself turning to short things, collections of stories, articles, essays. Here, for your delectation, and in short takes, because naturally I didn’t have time to give them the kind of long reviews I usually write, are some I’ve found particularly enchanting or exciting.

Like literary Christmas stockings, all the books below are stuffed with small enticing treasures.

FOF award-winning author, Linda Wolfe, has published eleven books and has contributed to numerous publications including New York Magazine, The New York Times, and served the board of the National Book Critics Circle for many years.

Honeydew: Stories

by Edith Pearlman

Little Brown.

SUSPENSEFUL STORYTELLING and SUMPTUOUS LANGUAGE is what you can expect from Honeydew, a collection of twenty tales by short story writer, Edith Pearlman. Pearlman’s last collection, Binocular Vision, won the National Books Critics Circle Award for fiction in 2011, an award only rarely given to a work of short stories. Alice Munro won it once, and interestingly Pearlman has often been compared to Munro. But she’s also been compared to Chekhov. The praise is no wonder. Pearlman is arguably today’s premier American short story writer. She has a voice uniquely her own and a range that takes her from realism to surrealism, from the intimacies of marriage or a mother-child relationship to broader concerns in foreign settings. She delves into souls, and slinks into hidden corners of social behavior; she is a master at presenting a character’s present  predicament and simultaneously giving us a glimpse into her or his future—the story of what happens after the story.

predicament and simultaneously giving us a glimpse into her or his future—the story of what happens after the story.

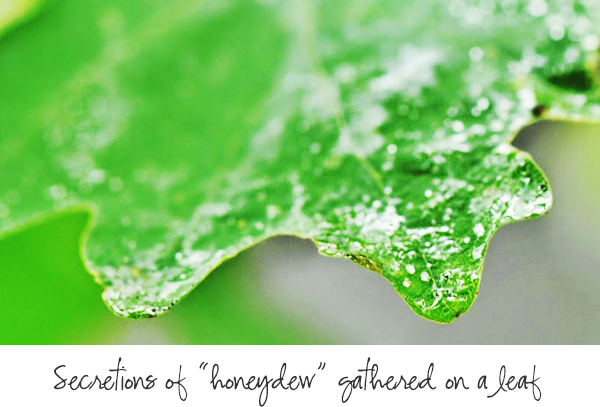

No one of her stories is quite like another. In “Tenderfoot,” a widowed pedicurist has romantic fantasies about a lonely, recently separated customer, only to realize that neither of them is really unattached. They are both still in mourning, she for her Marine husband, a man she allowed to re-enlist when he was really too old to go back into conflict, he for the people in a car crash that he and his wife witnessed, and who, despite the wife’s entreaties, he had sped past, unwilling to stop and at best, provide aid, at worst, extract corpses. In “Dream Children,” an apparently devoted father, like a primitive who dons the mask of a fearsome animal to ward off attack by one, draws pictures of deformed children presumably as a way of protecting his family from catastrophe. In the title story, “Honeydew,” an anorexic middle school student at a private boarding school is losing weight at an alarming rate. She wants to be an insect, her professor father explains, in this very strange story. And indeed, Emily is fascinated by Coccidae—ants. “Emily liked the story of Moses leading the starving Israelites into the desert. Insects came to their rescue. The manna, which Exodus describes as a fine frost was thought to be a miracle from God, but it was really Coccidae excrement… Nomads still eat it. It is called honeydew.”

Pearlman enters the mind of this odd child, but she also gives us the girl’s perplexed mother, that complicated father, who is having an affair with the school’s headmistress, and the headmistress herself, pregnant by the father and despairing of her future till she comes up with an unexpected solution to her dilemma. It’s enough for a novel, and in the hands of another author, it might have been one. But Pearlman has never written a novel. She’s thought about doing one, she says, but has always returned to what she does best: stories that are as packed with incident and characters as in many a longer work. She’s a fascinating writer.

The Assassination

of Margaret Thatcher

by Hilary Mantel

Henry Holt.

SLEEK and STARTLING, this book of ten short stories by the incomparable Hilary Mantel, makes for bewitching reading because Mantel is a magician of an author, with all kinds of literary chicanery up her sleeve. Her Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies, for all their serious intent—the rehabilitation of the much-maligned Thomas Cromwell—were sly books, full of surprises and written with a mix of stately and slangy language that has permanently altered the future of the historical novel. The ten every-word-counts stories collected here are also brilliant, sly, and filled with surprises. The title story, “The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher,” is a wish-fulfillment dream. “Comma” and “How Shall I Know You?” are nightmares. “Offences Against the Person” and “The Long QT” are break-your-heart sad. Every story in the volume is another surprise.

Mantel can make you see a character more vividly than you might with your own eyes. Here’s an unnamed narrator looking at a young man she encounters in a train station: “I gazed up into his face: he had large blue eyes, a shy yet confident set to him; he was six foot and lightly bronzed, strong but softly polite, his jacket of indigo linen artfully crumpled, his shirt a dazzling white; he was, in all, so clean, so sweet, so golden, that I backed off, afraid he must be American and about to convert me to some cult.” (After that little dig at us Americans, the narrator goes on to think, “I’d quite like to go to bed with someone of that ilk, by way of a change. Wasn’t everybody due a change?”)

In addition, Mantel can be as scary as Stephen King. In “How Shall I Know You?” the narrator must spend the night in a dilapidated hotel where her bed has “a turd-colored candlewick cover,” a chair whose plush buttoned back has “a gray rime of dust, like navel fluff, accumulated behind each of its buttons,” and there are closets that smell “as if there were a corpse in the room.” In “Sorry To Disturb,” a story that goes back in time to the author’s days in Saudi Arabia, she begins with: “In those days, the doorbell didn’t ring often, and if it did I would draw back into the body of the house… Through the spy hole I saw a distraught man in a crumpled, silver-gray suit: thirties, Asian… He looked so fraught that his sweat could have been tears. I opened the door.”

One wants to cry out, “No, don’t do it!” From the get-go, from the very first paragraph, the author has sent chills through the reader, yet the uninvited visitor in this tale, first published in 2009, doesn’t do anything as disturbing as it seems at first that he will.

No matter. Mantel was so intrigued by the creepy possibilities inherent in opening the door to a stranger that this year, five years after writing “Sorry,” she used the same set-up to produce the title story in this collection, “The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher: August 6th, 1983.” “The Assassination” begins, “I was putting my Perrier water in the fridge when the doorbell rang… On the landing—or rather on the front step, as I was alone up there—stood a man in a cheap quilted jacket. My innocent thought was, ‘Here is Duggan’s son. ‘Boiler?’ I said. ‘Right,’ he said.” Soon after the stranger heaves himself into the narrator’s flat, she grows suspicious of him. “’I was expecting a plumber,’” she says. “’You shouldn’t just walk in.’ “‘You opened the door,’” the man replies ominously.

This time around, admitting the stranger results in an act that is shocking and violent, indeed, and this time around Mantel has produced her most unusual story—an enigmatic political and psychological thriller.

It’s as if in this book, distancing herself from her present reputation as the consummate producer of historical fiction, Mantel is laying claim to being an heir to Edgar Allen Poe, to being a consummate producer of phobia fiction.

The Fame Lunches

by Daphne Merkin

FSG.

EDGY, IMPERTINENT, and EXHILARATING, The Fame Lunches is a collection of 45 of Merkin’s previously published essays on cultural icons, film and literary stars, and, as one critic put it, “the comings and goings of the zeitgeist.” Merkin is one hell of a book critic, and she’s so smart about our society you want to weep with jealousy. She’s drawn to the emotionally wounded, like Mike Tyson and Michael Jackson, and she’s acerbic and tough on folks like Nicole Kidman and Scott Fitzgerald. But the person she’s toughest on is her self. I love the personal essays included in the book. There’s a dynamite one about money, “Our Money, Ourselves,” which ends with Merkin, who was born into a wealthy family, breaking up with an equally well-off lover. “I yearned for a ‘what’s mine is yours’ embrace, for a plenitude of cherries; he had been divorced twice and feared being exploited—giving with no guarantee of return. One night, just when it seemed we had settled into the rituals of domestic togetherness, he reminded me, as I was getting into bed, that I owed him money for a dry-cleaning bill. There it was again: It’s only money. It’s only everything.”

“We broke up the next day.”

Even better is her essay on being overweight, “In My Head I’m Always Thin.” She tells us that although she was slender as a girl and young woman, but by the time she reached her fifties she had become “inarguably overweight.” “I’d certainly sized myself out of Barney’s,” she writes, “and most of the clothes I coveted, which assumed the presence of a waist, a narrow back, and thin upper arms. Both waist and back had widened to such an extent that I never wore anything tucked in and sought out pants with elastic waistbands.” Merkin, wrestling with weight problems yet trying to hold onto inner feelings of still being an attractive woman, believes that our society has “pathologized the problem of obesity beyond any corroborating medical reality,” and suggests that the bulk of medical evidence indicates that it is more dangerous to be 5 pounds ‘underweight’ than 75 pounds ‘overweight.’

Take that, you obsessive dieters!

A Curious Career

by Lynn Barber

Bloomsbury.

FRANK and FUNNY, Lynn Barber, Britain’s premier celebrity interviewer, the Barbara Walters of their print scene, has written a lively memoir about herself, her interviewing techniques, and some of the numerous celebs she’s interviewed. There’s Nureyev, Vanessa Redgrave, Oliver Stone, William Hurt, Norman Mailer, Damien Hirst, David Hockney Christopher Hitchens, Marianne Faithfull, and lots of others. But mostly this is a book about Barber herself. “My ambition as a child was to be some sort of writer,” she tells us, “But my hobby as a child was being nosy.” She’s still nosy, she explains, because she wants to understand other people. To that end, ideally she likes to do her interviews in a subject’s home. “You can learn so much about them. Are they super-neat or chaotic? Do they have more photographs of their family, or of themselves? A trip to the loo is often instructive—it’s where people put their awards and cartoons—things they’re proud of and want visitors to see but without too  obviously showing off. Of course if you can go to their own bathroom, rather than the guest cloakroom, better still—look for the pills!”

obviously showing off. Of course if you can go to their own bathroom, rather than the guest cloakroom, better still—look for the pills!”

It’s fun to learn that James Stewart, at 75, refused to be photographed, because he thought he looked old. That Salvador Dali’s favorite sexual activity was masturbation. That Ali McGraw considered herself an alcoholic because she once drank a whole bottle of wine over dinner. (“Californians,” Barber, a bon vivant, scoffs, “consider anyone who drinks more than one glass of wine an alcoholic.”) Robert Redford sat stony-faced when, during her interview with him, she had a sudden fit of coughing. “He sat there with a bottle of water beside him, failing to offer me any,” she writes, and seemed to be “furious that I might be giving him germs.” And here’s Norman Mailer: “‘Great fucks are very rare! Great fucks are rare enough that they have to be respected!’ And yes, he’s of the opinion that womenshould have babies as souvenirs of great fucks.”

Barber is definitely Fab Over Fifty. In fact she’s Sensational Over Seventy. Having just reached that marker, she’s noticed that “there are two basic stereotypes for women my age and older. You can either be a sweet old biddy, patting kiddies on the head and saying how you long to put your feet up and have a nice cup of tea. Or you can be a wicked witch who scares people stiff. I’ll go for the latter.” Because, she sums it all up, “Basically it’s a choice between do I want to feared or do I want to be patronized and frankly, I prefer the former.”

You’ll like this gal!

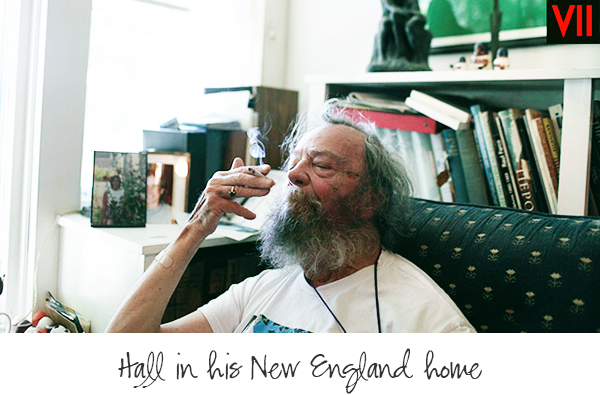

Essays After Eighty

by Donald Hall

Houghton Mifflin.

DOWN-TO-EARTH OBSERVATIONS and HIGH WISDOM are the hallmarks of the essays of Donald Hall. Hall, who is 86-years old, was Poet Laureate in 2006-7, and won a National Medal of Arts in 2010. Despite the fact that he has to take his “first nap of the day at 9:30 AM,” and must use a walker to get around, he’s still having go-for-broke, full days, living the life of the mind. He writes on subjects like why he continues to smoke, the friends he’s lost, the quest for immortality, his feelings about realizing death cannot be far away, and his love life and two marriages. I especially like his advice to other writers: “When writing memoir, don’t say, ‘I remember that in my childhood nothing happened to me.’ Say, ‘In childhood nothing happened.’ When writing essays, “Almost always… the end goes on too long. ‘In case you don’t get it, this is what I just said.’ Cut it out. Let the words flash a conclusion, then get out of the way.” And, “Essays, like poems and stories and novels, marry heaven and hell. Contradiction is the cellular structure of life… if the essay doesn’t include contraries, however small they may be, the essay fails.”

Best of all, are his epigrammatic remarks, like this delightfully cynical one: “There are no happy endings, because if things are happy, they haven’t ended yet.”