Two acclaimed members of New York’s literati have published memoirs at the same time.

![]()

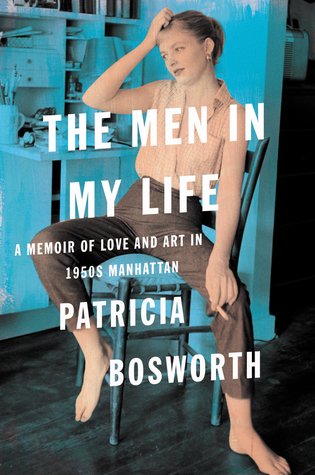

THE MEN IN MY LIFE: A Memoir of Love and Art in 1950s Manhattan

THE MEN IN MY LIFE: A Memoir of Love and Art in 1950s Manhattan

by Patricia Bosworth

HarperCollins.

Bosworth, who has written best-selling biographies about movie magnificos like Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, and Jane Fonda, as well as an incisive biography of photographer Diane Arbus, and a searing account about the life and death of her father, famed civil rights lawyer Bartley Crum, has finally, in The Men in My Life, given us an autobiography that is harrowing, scintillating, and, ultimately, profoundly inspiring.

The harrowing part comes first. Two of the three men who figure prominently in this book, Bosworth’s beloved younger brother, as well as her distinguished father, will commit suicide. The third, Jason Bean, is a sociopathic painter, whose only real aesthetic talent was for con-artistry, who swept Bosworth off her feet while she was a freshman in college.

Flattered by his attentions — and like so many young women back in the early 1950s, sure that if you had sex with a man it must mean you’re in love with him — she marries this ne’er-do-well. Giving up dorm life, she goes to live with him in a setting only Hitchcock could dream up: a seedy Bronx apartment presided over by a taciturn wheelchair-bound grandmother and a flock of a hundred noisy birds. Jason turns over to Bosworth the job of feeding the creatures and cleaning out their numerous cages, even though she’s frightened of birds. She acquiesces, although she is slowly coming to realize that her Prince Charming is “to put it mildly, not a very nice person. In fact, he was self-involved, hypercritical, and bad-tempered.”

No matter. Soon Bosworth, who’d been raised in a home abundant with maids, was doing all the work of the household, shopping at the A & P, taking the dirty clothes to the Laundromat, even cooking dinners for Jason, Grandma and a sister-in-law who was also staying in the crowded apartment. But here’s quintessential Bosworth: “Rather than resenting it, I took all of it as a challenge. I felt as if I was on a crazy adventure. Not all of it was pleasant, but I took it as a learning experience.”

This astonishing fortitude will stand her in good stead throughout her life and, most immediately, when it becomes clear that Jason, who is not above smacking his wife around, is not only abusive but a gold-digger. Lazy, he’d been figuring Bosworth’s well-to-do parents would provide for the pair. But to his dismay, they decline to do so. Unfazed, the plucky Bosworth steps up to the plate and takes on the job of supporting both her husband and herself.

She starts out with waitressing, then, via family connections, gets modeling jobs. A pretty fresh-faced young woman, soon she is posing for Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and McCall’s magazines, making good money, and obligingly turning it over to her grasping mate.

It took Bosworth several years to extricate herself from this marriage, but in time she did. And that’s when the book becomes scintillating. Now, as she starts looking for and obtaining work in the theatre and on TV, the author takes us goes on truly heady adventures, becoming a member of the prestigious Actor’s Studio, studying her craft under luminaries like Elia Kazan and Lee Strasberg, wrapping her arms around the sexy waist of Steve McQueen, who takes her for a motorcycle ride, cabbing uptown alongside Marilyn Monroe (and noticing “she had dirt under her fingernails,”) partying with Norman Mailer (and noticing he “had big ears”), as well as with Henry Fonda, Julie Andrews, Truman Capote, and numerous other celebrities. In time, she will even make it to the movies, playing opposite Audrey Hepburn in A Nun’s Story.

It took Bosworth several years to extricate herself from this marriage, but in time she did. And that’s when the book becomes scintillating. Now, as she starts looking for and obtaining work in the theatre and on TV, the author takes us goes on truly heady adventures, becoming a member of the prestigious Actor’s Studio, studying her craft under luminaries like Elia Kazan and Lee Strasberg, wrapping her arms around the sexy waist of Steve McQueen, who takes her for a motorcycle ride, cabbing uptown alongside Marilyn Monroe (and noticing “she had dirt under her fingernails,”) partying with Norman Mailer (and noticing he “had big ears”), as well as with Henry Fonda, Julie Andrews, Truman Capote, and numerous other celebrities. In time, she will even make it to the movies, playing opposite Audrey Hepburn in A Nun’s Story.

But for all her successes, Bosworth is still a troubled person. Her emotions, she tells us, have been “in essence, frozen” ever since the suicides of her brother and father. Acting makes her anxious. Sometimes she feels a lot “like a failure.” She sleeps around “indiscriminately.” She finds her diaphragm uncomfortable so stops using it. She gets pregnant. Has a less than ideal abortion. Keeps having bad judgment about the irresponsible men she chooses to take a place in her life.

Yet I said earlier that the book is inspiring. How so? Because ultimately, Bosworth pulls herself together. She falls in love with a “gentle, courtly” and protective man. She changes careers from acting to writing, which is less stressful for her, and makes a name for herself as a journalist and biographer. Her frozen emotions melt, and The Men in My Life becomes the story of a young woman’s journey from an atrocious lack of self-esteem to a prideful belief in herself and her many talents.

![]()

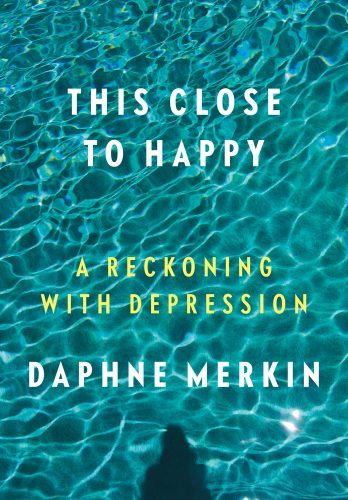

THIS CLOSE TO HAPPY: A Reckoning With Depression

THIS CLOSE TO HAPPY: A Reckoning With Depression

by Daphne Merkin

FSG.

If Bosworth had to endure the sorrow and survivor’s guilt that fester after the suicides of family members, gifted essayist Merkin has had to endure episodes of such profound depression that she yearned to find within herself the wherewithal and psychic strength to commit suicide. Merkin makes depression so vivid one can almost feel, along with her, “that roaring pain inside your head that feels physical but has no somatic correlation that can be addressed and treated,” and the way time hangs so heavy when your mood hits rock bottom that it’s “like a vise around your neck.”

Merkin reminds us that depression has been recognized as a specific and serious condition throughout history, going under different names at different times, from melancholia to malaise, the blues to the mean reds. She informs us that depression is a global problem, affecting 350 million people worldwide, and that in the United States in 2012, some 16 million people had at least one major depressive episode.But mostly she confides in us, writing with great frankness about her recurrent hospitalizations in various psychiatric hospitals, the endless parade of psychiatrists she has consulted, her dysfunctional family, and her often difficult relationships with friends and even with her daughter. Along the way, she makes the fascinating observation that men who suffer from depression seem content to accept today’s prevailing psychological theory of the disease’s cause, namely that the condition results from a flaw in biology, while women sufferers are inclined to look for the roots of their illness in themselves or in their families.

Merkin is a great blamer, but to her credit, she’s as hard on herself as she is on everyone else she faults. Chiefly that’s her mother, who relegates the care of her brood of six children to a Dickensian nanny, a slapper and pincher and hair-puller who never provides enough food. Merkin has told this story before, in several of her essays. But like the ancient mariner, she seems condemned to tell it over and over again. It’s the story of the quintessential poor little rich girl, reared on Park Avenue, in a wealthy Orthodox Jewish household replete with everything except love. Little Daphne discovers that the only way to get her preoccupied mother’s unreserved attention is to be sick, and Big Daphne speculates as to whether the habit of using real or feigned sickness to gain attention can account for her daughter’s episodes of depression.

Merkin is an exciting writer, every sentence a gem, every paragraph a treasure, no matter how sad the subject matter. I’d like to spell out what’s so special about her prose, but I don’t think I can match the clarity and precision of what she herself, speaking of that self in the third person, has written: “She is appreciated for her gimlet eye, her curiosity, her wry humor and warmth.”

Merkin is an exciting writer, every sentence a gem, every paragraph a treasure, no matter how sad the subject matter. I’d like to spell out what’s so special about her prose, but I don’t think I can match the clarity and precision of what she herself, speaking of that self in the third person, has written: “She is appreciated for her gimlet eye, her curiosity, her wry humor and warmth.”

Of course, being Merkin, she concludes this self-praise with, “from the outside in, her life might strike others as good, if not enviable; she knows this on some level but the knowledge dries up as the wind howls through her, reminding her that she feels barren and lost and quite without hope.”

Award-winning author and FOF Book Critic, Linda Wolfe, has published 11 books, contributed to numerous publications including New York Magazine and The New York Times, and served on the board of the National Book Critics Circle.

Award-winning author and FOF Book Critic, Linda Wolfe, has published 11 books, contributed to numerous publications including New York Magazine and The New York Times, and served on the board of the National Book Critics Circle.