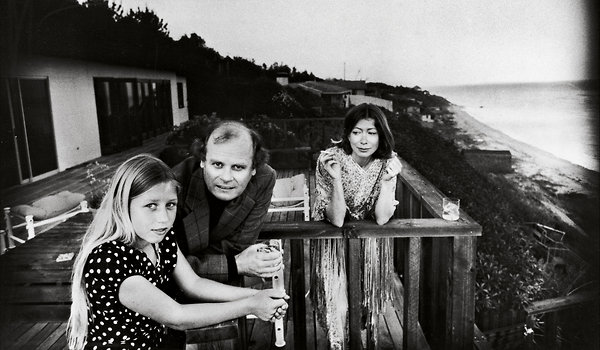

Famous author, Joan Didion, was interviewed on TV this weekend about her new book, Blue Nights, a memoir about her adopted daughter, Quintana, who died from pancreatitis in 2005, at age 39. I bought the book and read it in a day since it’s a short work. I like the way FOF Joan writes. Her concise sentences paint vivid images, such as the LA fog obscuring her Malibu driveway; Quintana’s nightmares about “The Broken Man,” an evil repairman who had come to lock her in the garage, and the 66 little dresses the baby received as presents.

Although Joan is a brilliant writer, her book leaves me wanting to know much more about her relationship with Quintana, indeed, about Quintana herself. Joan writes about her grief, but I don’t feel her loss. I remember the moving story of Eric, a 17-year-old diagnosed with leukemia, that was written by his mother, Doris Lund. My heart went out to her and to her dying son. That book was written from the heart; Joan’s seems written from somewhere else—perhaps the brain. It intellectualizes her tragedy, her concern about her current physical and mental states, what happens when Quintana learns the identity of her “biological” mother. I wanted to be moved more, but I’m not sure why.

The worst tragedy that can befall us is the loss of a child. Joan is most powerful when she writes about losing, not her daughter, but “that sense of the possible.”

“One day we are absorbed by dressing well, following the news, keeping up, coping, what we might call staying alive; the next day we are not. One day we are turning the pages of whatever has arrived in the day’s mail with real enthusiasm—maybe it is Vogue, maybe it is Foreign Affairs, whatever it is we are intensely interested, pleased to have this handbook to keeping up, this key to staying alive—yet the next day we are walking uptown on Madison past Barney’s and Armani or on Park past the Council on Foreign Relations and we are not even glancing at their windows. One day we are looking at the Magnum photograph of Sophia Loren at the Christian Dior show in Paris in 1968 and thinking yes, it could be me, I could wear that dress, I was in Paris that year; a blink of the eye later we are in one or another doctor’s office being told what has already gone wrong, why we will never again wear the same red sandals with the four-inch heels, never again wear the gold hoop earrings, the enameled beads, never now wear the dress Sophia Loren is wearing. The sun damage inflicted when we swam off the raft in our twenties against all advice is only now surfacing (we were told not to burn, we were told what would happen, we were told to wear sunscreen, we ignored all warnings): melanoma, squamous cell, long hours now spent watching the dermatologist carve out the carcinomas with the names we do not want to hear.

“Long hours now spent getting the intravenous infusions of the medication that promises to replace the bone lost to aging.

“Long hours now spent getting the intravenous infusions and wondering why the Vitamin D we thought we were accumulating by not wearing sunscreen failed to realize its bone-building potential.”

I am sorry that Joan lost her daughter and, two years before, her husband of many decades, writer John Gregory Dunne. I am also sorry that Joan feels she’s losing that “sense of the possible.” That is another tragedy for her.

One Response to “Joan’s language of loss”

Patricia C. says:

I have also read this book. It was beautiful and sad, and heartbreaking. I can feel her pain at realizing so much of the future is now lost. There is no second chance to make anything right after death has taken the one you love. Joan always seemed to be questioning if she had been a good enough mother to Quintana. How will she ever know? I agree that I would have liked to know more about Quintana herself. Maybe the author couldn’t expose the truly horrific pain that one would feel after losing a child. The story does feel a little like we can know this much, but not everything, almost like that would be asking the impossible.