Best Books Of 2016

Author and FOFriend, Linda Wolfe, recommends five books for the new year.

FOF award-winning author, Linda Wolfe, recently published her powerful book, My Daughter, Myself: An Unexpected Journey. She has published eleven books and has contributed to numerous publications including New York Magazine, The New York Times, and served the board of the National Book Critics Circle for many years. Her latest reviews capture everything from 1960s Kabul to present-day hostages in Somalia.

FOF award-winning author, Linda Wolfe, recently published her powerful book, My Daughter, Myself: An Unexpected Journey. She has published eleven books and has contributed to numerous publications including New York Magazine, The New York Times, and served the board of the National Book Critics Circle for many years. Her latest reviews capture everything from 1960s Kabul to present-day hostages in Somalia.

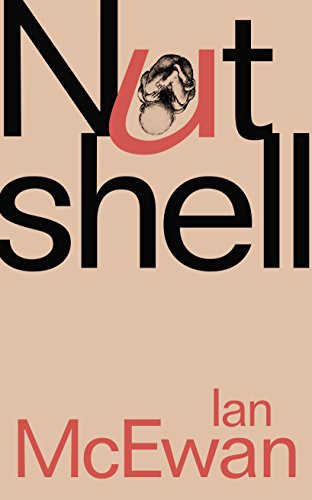

NUTSHELL

by Ian McEwan

Nan Talese/Doubleday.

If you haven’t already read this, put buying it at the top of your To Do list. And give it to yourself, not someone else, though that’s not a bad idea, either. With Nutshell, the masterful McEwan, of Atonement and Saturday fame, has produced another masterpiece. This, despite its absurd premise – or maybe because of it. The absurdity? The story is told by a foetus.

He’s a clever little fella. Knows all about wine, especially his mother’s favorites, French burgundy and a good Sancerre, which come to him, he explains, “decanted through her healthy placenta.” Knows too all about Norway, with its generous social provisions, and Italy with its excellent regional cuisine. How is this possible? It’s because, he tells us, “I listen. My mother likes the radio and prefers talk to music…I hear, above the launderette din of stomach and bowels, the news, wellspring of all bad dreams. I listen closely to analysis and dissent.”

He also listens to his mother’s conversations. And, poor little eavesdropper, he overhears her plotting with her lover, his uncle, to murder his father. She is Trudy. He is Claude. Get it? Nutshell is, in a nutshell, Shakespeare’s Hamlet as experienced and related by an unborn baby. This one sure doesn’t like Claude. “Not everyone knows what it is to have your father’s rival’s penis inches from your nose,” he says. “By this late stage [of pregnancy], they should be refraining on my behalf. Courtesy, if not clinical judgment, demands it. I close my eyes. I grit my gums. I brace myself against the uterine walls. This turbulence would shake the wings off a Boeing.”

The book is hilarious. Its also wondrous, with every sentence chiseled to perfection – perhaps in homage to Shakespeare. Most delicious of all, Nutshell is a page turner. Its suspense builds and climbs as we wonder if this older-than-his-years, or even older-than-his-months little creature who’s telling us the story will be able to prevent the murder.

THE NEWS OF THE WORLD

THE NEWS OF THE WORLD

by Paulette Jiles

William Morrow.

This book had me reading on the edge of my seat and metaphorically biting my nails. A historical novel, it’s set in the wilds of Texas in the years immediately following the Civil War. The story is told by elderly Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd, who makes his living by driving his covered wagon to isolated small towns where he reads the news of the world to settlers with no access to newspapers. One day, he’s asked by a federal agent to take on the task of transporting to her remaining family members a ten-year-old child who, at the age of six, had been taken captive by the Kiowa Indians after they scalped her German-American parents.

The girl is a handful. She doesn’t want to be rescued. She considers herself a Kiowa, and has become very attached to her captors. (Apparently, we learn in an endnote, this was common among children taken by Indians; very few of them wished to be rescued and returned to relatives.) She has no memory of what her original name was, so Kidd gives her a name: Johanna.

At first the Captain finds the girl, with her blond braids flaunting bits of stick, her immobile face, and her icy blue-eyed stare, “malign.” She finds him hateful, and proves to be a kicking, screaming, disobedient passenger, always trying to run away. But after they are attacked by truly malign men, and against great odds they together manage to fight them off, the unlikely pair bonds. In time, Johanna, who has learned to call herself “Cho-Hana,” comes to love the “Kep-dun,” who one day she dubs “Kontah,” Grandfather in the Kiowa language. The Captain himself has learned to admire his spunky little charge, and like a real grandfather, dotes on her and longs to see her have a happy future. But trouble awaits when the pair finally makes it to San Antonio, where Johanna’s remaining relatives live.

Jiles is a poet, and she knows how to use her music to play upon the heartstrings. I defy you not to shed a tear, as I did, at what happens to Johanna when she is reunited with her family – and to pray that once again the Captain will find the strength to rescue her.

COMMONWEALTH

COMMONWEALTH

by Ann Patchett

HarperCollins.

Patchett is unpredictable as a novelist, and I don’t mean as regards her art, which is reliably wondrous. I’m referring to the kind of tale she tells in each book, its whos and wheres and wherefores. Commonwealth starts out in California as the story of a married couple who fall in love with other people, divorce their partners, and try to meld their unwieldy bunch of children, three of his, two of hers, into a viable extended family. They’re successful at this. The children become very close. But they are uneasy with their new stepparents and angry at the parents who broke up their original families.

What we get is a tapestry, a complex and exquisite weave of different threads, in which each thread is the tale of one of those children or parents relating what happens to them over a long period of time. Fifty years, to be exact, enough time for the children to grow up and old, and the parents to grow aged. There are lots of characters, lots of threads, a sister who becomes a lawyer, another who becomes a Zen monk, a misfit of a brother who bears a burden of guilt all his life about a tragedy that befell another brother, and, most memorably, the gentle Franny, who falls in love with a writer much older than she is and makes the mistake of telling him the story of her family, only to see him use it, to her embarrassment, and for his own self-aggrandizement. Patchett, treating all her characters with abounding compassion, makes every one of them so vivid and recognizable that you’ll be as fascinated by how they develop and change over the years as you are in how time treats your friends.

Interestingly, at first Commonwealth seems like a book about extended families, of which we have read many in recent years. But it turns out to be about something newer, and and more important. Patchett’s characters marry, and have children, and get divorced, and some of them remarry and acquire new children, and their children marry and have children, and some of them get divorced and remarried and also acquire new children, so that the “family” keeps growing and expanding. One of the book’s final, stunning scenes shows us that not only do today’s extended families grow ever larger, but that the very idea of family is changing. When Franny’s mother, late in life, marries a man named Jack Dine, and Franny goes to their Christmas party, she realizes that she can’t keep everyone there straight. “She knew the Dine boys, that’s what they were called late into their fifties, but their wives and second wives confused her, their children, in some cases two sets, some grown and married, others still small…There were members of the Dine family who considered her in some vague sense to be a sister, a cousin, a daughter, an aunt. She couldn’t follow all the lines out in every direction: all the people to whom she was by marriage mysteriously related.”

I think Commonwealth could well have been entitled, The Way We Live Now, like Trollope’s book of that title, for what it really is about is a world in which increasingly the very word family has come to seem something altogether new.

THE RETURN: Fathers, Sons and the Land In Between

THE RETURN: Fathers, Sons and the Land In Between

by Hisham Matar

Random House.

In 2007, when I first fell in love with the work of Libyan-born writer Hisham Matar, it was because I had just read his novel, In the Country of Men, a polished, psychologically astute novel about a little boy who inadvertently betrays his father to the jailers of a repressive regime. The child’s grief at the loss of his father’s presence, plus the burden of guilt he feels for causing that loss, were haunting. I did not know until I read Matar’s eloquent memoir, The Return, that at the time he was writing In the Country, the author was himself struggling with grief over the loss of his own father to the repressive regime of Qaddaffi, and even struggling, with a kind of survivor’s guilt, what he calls, “the guilt of having lived a free life,” for he and the rest of his family had fled the Middle East to live zin exile in London.

Matar’s father, Jaballah, had not had a free life. An outspoken opponent of the repressive Qaddaffi regime, he had been kidnapped in 1990, imprisoned, and after a few years during which he wrote letters to his family which were smuggled out of Libya by political supporters, never heard from again. Was he still a prisoner, held in some miserable dungeon, like the one fellow prisoners called, “The Mouth of Hell”? Or was he dead? The uncertainty turned Matar, then nineteen years old, “into a bridled animal, cautious and quiet. I could not stop thinking of the detestable things that were surely happening to my father as I bathed, sat down to eat….I stopped speaking. I hardly left my London flat,” he writes, and, “You make a man disappear to silence him, but also to narrow the minds of those left behind, to pervert their soul and limit their imagination. When Qaddafi took my father, he placed me in a space not much bigger than the cell Father was in.”

During the years that followed the kidnapping, Matar, his mother, and his brother, Riad, spent endless hours trying to raise public awareness of what had happened to Jaballa, and to arouse British diplomats into finding out what they could about his whereabouts, all to no avail. So in 2012, after the fall of Qaddaffi and before Libya fell victim to competing militias including Al Qaida, when for a brief time the country was peaceful, Matar went there to see if he could learn something of his father’s fate.

The Return is the story of that trip. Matar travels with his mother and brother, and the three of them manage to find and reunite with relatives they haven’t seen in years. We visit along with them, discovering the Libya that was, and its rich culture and fascinating traditions.

The book is heartbreaking. Matar learns of a prisoner who may or may not have been his father (but seems likely to have been), a man who recites Libyan poetry from his cell a night, and then one night is heard no more. He learns the details of Qaddaffi’s notorious 1996 massacre of twelve hundred prisoners (his father was most likely one of the men brutally killed that day). And he learns how his father, surviving for many years in the most horrendous circumstances, became a symbol to his fellow prisoners of all that was once steadfast and noble in Libya.

SWING TIME

SWING TIME

by Zadie Smith

Penguin Press.

I’m not a big fan of Elena Ferrante. Perhaps it’s the fault of the translator, but I find the language of her acclaimed Neopolitan novels flat and dull. But of course, like everyone else, I’ve been a sucker for the books’ subject – female friendship — a matter so important to so many of us females, but so little written about. Well, no need to slug through those Naples novels. Zadie Smith of White Teeth fame, arguably England’s most renowned novelist and certainly its liveliest stylist, has just come out with Swing Time, a novel about female friendship which pops and sizzles and rocks. It’s all here, the passionate attachments we women form with friends, first when we’re young, later on, throughout our lives, the way we measure our lives against those of our friends, the way our friendships support and sustain us and the way they can grow stale, can wither with time or distance or achievement, or die sudden deaths from envy or betrayal. Not to mention the way we never, no matter what, forget our first best friends.

The unnamed narrator of Swing Time lives in one of London’s depressing housing projects. She meets the girl who will become her best friend, a pretty child named Tracey, also the denizen of a housing project, when she’s seven years old, at an after school dance group. “There were many other girls present,” she tells us, “but for obvious reasons we noticed each other, the similarities and differences, as girls will. Our shade of brown was exactly the same – as if one piece of tan material had been cut to make us both – and our freckles gathered in the same areas.” Each girl has one white and one black parent. The narrator’s mother is black, a Jamaican immigrant bent on climbing up and away from the projects through education and discipline, her father a white postal worker with little ambition beyond caring for his daughter. Tracey’s mother is white, permissive, free-spending, imbued with bad taste, and determined to see Tracey, who has talent as a dancer, become a star. Tracey’s father, who rarely comes to see his wife or his daughter, is a gambler and petty thief; he’s been in prison, but Tracey boasts when he’s absent that it’s because he’s a back-up dancer traveling with Michael Jackson.

The narrator shares Tracey’s love of dancing, though not her talent. No matter. Together they bond over dance VHS tapes, spending endless hours watching Fred Astaire and other hoofers do their routines. To both girls, it seems that their friendship is forever. But time and the differing aspirations of their mothers intervene. Tracey becomes not a star but a minor chorus line dancer and the narrator, after attending university, becomes the personal assistant of a famous singing star, an international celebrity patterned on Madonna and named Aimee.

Along the way the narrator will have boyfriends — I especially liked her college beau Rakim, who wore “skinny dreadlocks to his shoulders, Converse All Stars in all weather, little round Lennon glasses. I thought he was the most beautiful man in all the world. He thought so, too.” She will travel, with Aimee, to distant places. New York offers to her “her first introduction to the possibilities of light, crashing through gaps in our curtains, transforming people and sidewalks and buildings into golden icons.” Gambia, where do-gooder Aimee wants to establish a girls school, offers “polygamy, misogyny, motherless children (my mother’s island childhood, only writ large, enshrined in custom).”

Along the way, the book will offer perceptive reflections on race and class, plans will be realized and thwarted, there will be scandals and betrayals, babies dubiously adopted, lovers lost and stolen, and friendships that teeter and totter yet offer identity and belonging in a world that rarely does. This is an action-packed cinematic novel that also thinks hard on its swiftly running feet.

by the publication here of their sparkling new works.

by the publication here of their sparkling new works.