Location: Sydney, Australia

Age: 56

Marital Status: Married

Education: Bethlehem College Ashfield, University of Sydney, Columbia University

If experience is the best preparation for writing, few authors can draw from a well as deep and diverse as that of FOF Geraldine Brooks. She grew up in Australia, studied journalism in New York, met her husband in the south of France, covered the Middle East and Africa for the Wall Street Journal, and now splits time—with her husband and sons—between Sydney and Martha’s Vineyard.

Perhaps that’s how Geraldine has become so masterful at immersing her readers in a place and time in history. In her best-selling novel, March, Geraldine vividly imagines Amos Alcott (Louisa May Alcott’s father) during his time as a chaplain in the Union army. Her meticulous historical research, along with her psychologically astute portrayal of shell shock and marriage, won the book the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

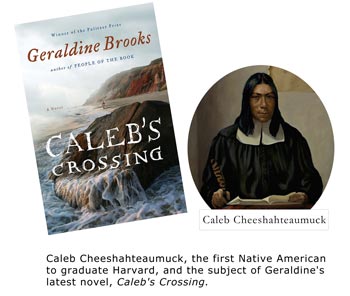

Geraldine’s most recent novel, Caleb’s Crossing, is no exception. This time, she imagines the life of Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck—the first Native American to graduate from Harvard, in 1665. The book is an illuminating portrait of colonial life, and also a heartbreaking romance that’s nearly impossible to put down.

We stole a few moments with Geraldine to learn about what drives and inspires her.

As a foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, you covered the Middle East extensively, and your first book centered on Muslim women. Is aging different for women in Muslim culture, compared to women in the West?

Women in the more repressive Muslim societies occasionally gain more freedom as they age, because they are no longer seen as dangerously sexual beings. So, for example, elderly women can sit with men and join in discussions in a way that would be impossible for younger women. There are also more multi-generational and extended family living arrangements, which makes for a less lonely and isolated old age and allows older women to have a role within the family as caretakers. Later, there are more hands to care for them when they need it.

Your novels seem to have a common thread of being set during times of duress the civil war, the Plague, persecution of Native Americans, wars in Europe; what appeals or inspires you about these times of great suffering?

This is when human nature is most exposed, for better and for worse. I suppose in some ways I am still chewing over the experiences I had as a foreign correspondent, often as a witness to contemporary crises. I use fiction now as a way to revisit and probe some of what I saw in those years.

When you were growing up Catholic in Australia, did you ever think you might end up a Jew in Massachusetts—having converted for your Jewish American husband?

One correction—I did not convert for my husband. I converted because of the history of the Jews. And the fact that Judaism is passed through the maternal line made me extremely unwilling be be the end of the line for a family that had made it through the Shoah, the Russian pogroms, the Roman sackings, etc. But yes, life is full of surprises and many things have occurred that I did not expect. I hope that will continue to be the case.

Your latest book chronicles a Native American student at Harvard in the 1600s—and his relationship with the English settlers in America at that time. What drew you to this subject?

Questions. How did it happen? What must it have been like? The urge to apply an informed imaginative empathy to the large silences and voids in the historical record regarding this remarkable young man and his journey between cultures.

Is there another current author who inspires you or whom you greatly admire? Why?

Bill McKibben, who writes peerlessly and honestly about the fate of our planet in this critical time of climate change.